Some personal experiences:

On my first day in China – before the arrival of colleagues – I was free. The rest of our time in China was very thoroughly programmed.

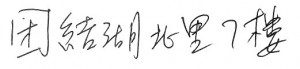

I glanced at the telephone directory. Tanzania was mentioned only once (apart from the Embassy). The entry read ‘China – Tanzania Joint Shipping Company’. It was to be found, apparently, at Juanjiehu Beili, Building No. 7 in Chaoyangpu. I asked the hotel receptionist to write this for me in Chinese and he produced without hesitation this:

I went outside for a taxi. The driver was friendly but we had no way of communicating and soon got lost. We were in the right area of the city but, as in much of Beijing, were dwarfed by row upon row of massive apartment blocks (obtaining accommodation in such blocks, I learnt later, is the dream of most of the inhabitants of the city). All these complexes had their No 7 building. About a dozen conversations and 30 minutes later we found a much smaller building which was also No 7. But this one, to my relief and delight, had a notice on the gate in English – ‘The China – Tanzania Joint Shipping Company.’

I climbed up one flight of stairs – having made sure that the taxi driver understood that he should wait – and wondered what my reception would be. Parastatal bureaucrats are never at their most welcoming when they come face to face with a journalist wanting to ask questions, regardless of whether the journalist is an amateur or a professional. And Chinese bureaucrats do have an ‘image’ problem.

Most of the offices were empty – it was Saturday morning – but I found two gentlemen at their desks. To my surprise they were friendly. Their contacts with Tanzania must have had a good effect. “How interesting” they more or less said “can we see a copy of the Bulletin of Tanzanian Affairs?” and what would I like to know?

Mr. Lei Zhen Ya, the Manager, explained that the company started in June 1967. It is run jointly by the two governments, each with a 50% share and was designed to serve trade between the two countries. The company began with four second-hand vessels but these have all since been replaced by new ones – the Ruvu, the Ruaha, the Pingku and the Shuniji with a total tonnage of some 60,000.

Originally the ships served the needs of the Tanzania-Zambia (TANZAM) railway and transported workers to Tanzania from China (I can remember the arrival one Sunday morning in Dar es Salaam of 1,000 of these workers all dressed identically in Mao suits and all issued with the same standard suitcase – how things have changed in China in recent years!) The ships also carried railway construction material.

It was at this stage in the conversation that I decided to make sure to interview, before leaving China, one or two of the early workers on the railway (there had been some 20,000 Chinese involved altogether) and hear how they looked back on their Tanzanian experience.

With the completion of the railway and a fall in the export from Tanzania of groundnuts and sisal, trade with Tanzania had gone down considerably. Nowadays cargo was sought wherever it could be found. Out of a total volume of 190,000 tons of goods transported by the company from China last year only about 7,000 tons went to Tanzania and no imports from Tanzania to China were carried. Furthermore, 1986 was the first year since the founding of the company that it had not made a profit. But relations with Tanzania remained warm and friendly. During the Cultural Revolution (a bitter memory to almost everyone to whom we spoke later) staff of the China-Tanzania Shipping Company had been left strictly alone and not persecuted in any way. Because of the link with a foreign friendly nation.

The 33 crew members of the two Chinese ships were all Chinese I learnt. The two Tanzanian ships had some 25 Tanzanian crew members and 7 Chinese including the captain.

Mr Lei said that the company was facing many problems but that the biggest by far was in obtaining sufficient cargo in a highly competitive market. But he was optimistic about the future: “With the recovery in Tanzania’s economy, trade will increase” he said.

My own job in China was in the Ministry of Agriculture. “Do you know of anyone who used to work on the TANZAM railway” I asked. Yes, said one of our counterparts, his own father was still working in the Ministry of Railways and had many friends who had worked in Tanzania.

Mrs Tang, who works as a Swahili interpreter in the Ministry of Agriculture told me how she had spent five years in Tanzania from 1973 on a State Farm growing rice at Mbarali in Mbeya region. “I was the one woman amongst 100 men” she said “and they could only communicate with Tanzanians through me”. It was hard work but she had enjoyed it very much. The Tanzanian people were very honest, (something which cannot be said for speakers at Chinese banquets whatever their nationality), very patient and easy to work with. And Swahili was so much easier to learn than English. She had been working only ten miles away from the railway and she knew many of those who had worked on it. She would get in touch with the Ministry of Railways and arrange for me to meet some of them.

I asked whether it had been easy to get people to volunteer to work in Tanzania in view of the harsh conditions at that time. “Yes indeed” Mrs . Tang said. “Only those with the best work records were allowed to go. Everyone wanted the chance. It wasn’t only the pay (50% higher than in China); it was a unique opportunity to see another part of the world.” But Mrs. Tang had had some second thoughts herself on her sixteenth day of sea-sickness on the way to Dar es Salaam.

Mr. Said Salim from Tanzania has been working in China longer than any other Tanzanian. 21 years. “They call me the Mayor of Beijing” he said. Originally he went there under the auspices of the organisation set up after the Bandung Conference as a journalist. Nowadays he works on the Swahili edition of a Chinese monthly magazine. He and his Zanzibari wife have four children, all taking university studies in Beijing. “They are more Chinese than the Chinese” he said. I asked him if he happened to know anyone who had worked on building the railway all those years ago. No, he said, but he dug into his archives and produced an article he had written in the ‘Afro-Asian Journalist’ (No. 1, Volume 9) in March 1972:

“Two events different from, though closely related to each other and antagonistic in character yet very commonly known in Tanzania and Zambia, came to pass in Africa on November 11th. It was on this day in 1965 when the Rhodesian white settlers unilaterally declared their independence …… and it was on this same day, in 1971, that the track laying on the 502 kilometre Dar es Salaam-Murimba section of the now world-shaking Tanzania-Zambia Railway (the biggest donor aided project in Africa) was completed … the two events seem like a ‘historical accident’; …. because of the existence of profound mutual trust among the three committed countries and the exigency China understands for both Tanzania and Zambia to have the railway built as soon as possible, preparation had commenced in March 1970 before the Protocol was even signed …. following immediately the tortuous surveys conducted from 1966 to 1970”.

One of our young interpreters said one day that he had found somebody who had worked on the railway. It seemed that nearly everyone we met knew somebody who knew somebody who knew something about Tanzania. But unfortunately this person lived at the other side of Beijing (a massive city) and he did not think it would be possible for us to meet.

As I learnt each day more about the history, the politics, the economy, the agriculture (most people are remarkably outspoken and the English language ‘Daily News’ explores every issue with astonishing freedom of expression) the similarity of experiences and, in particular, the ‘political language’ in China and Tanzania became more and more apparent.

China had its ‘Great Leap Forward’, its nationalisation of private businesses, collectivisation of agriculture; Tanzania had its ‘Arusha Declaration’ and its villagisation.

And now, many years later, Tanzania has its ‘Economic Recovery Programme’ and its ‘Structural Adjustment’. China has its ‘Economic Reconstruction and Structural Reform’.

The decisive 13th Party Congress attended by 1,926 Chinese delegates in October 1987 found some echo in the ‘Third National Party Conference’ attended by 1,931 delegates in Dodoma in the same month of the same year. The Chinese Party Congress made what was described as ‘a refined and systematic exposition on the theory of the primary stage (ie. the present stage) of socialism in China.’ It reaffirmed ‘the Party’s pledge to build socialism with Chinese characteristics’. But it noted that a small number of Party members were engaging in tax evasion, smuggling, bribery, moral turpitude, breach of discipline …. ‘ And in Dodoma. Mwalimu Nyerere had spoken of ‘some dishonest public servants and unscrupulous individuals who were taking advantage of the severe economic difficulties to enrich themselves.’ (Bulletin No. 29)

The 13th Congress clearly stated that the private economic sector in China should be allowed to develop to a certain extent. ‘With the objective of common prosperity in mind, we should encourage some people to become well-off first through honest work and lawful business operations’. A sentiment surely widely understood in today’s Tanzania.

And in both countries the reforms are showing results. Chinese officials speak of a new vitality in the country’s economy – a 103% increase in GNP, a 118% increase in industrial and agricultural output, 130% improvement in per capita income and, most spectacular of all (it is necessary to queue to climb the Great Wall or see the Terracotta Warriors) a 480% increase in income from tourism since the reforms began. And in Tanzania too, important gains can be seen, Growth up significantly for two successive years, substantially increased production of crops and so on.

But China has been making changes much more rapidly than Tanzania. The new ‘Responsibility System’ has decentralised decision making and the foreign investment code has brought about massive foreign investment all over the country. Factories are springing up everywhere.

And, just as the rate of inflation, especially in urban areas, dominates conversation in Tanzania, in China I learnt that, whereas reform in the rural areas brought almost immediate benefits for farmers, urban residents felt that the most noticeable feature of reform was inflation.

Tanzania has just devalued its currency. And, according to the December 3 issue of the Economist, China seems likely soon to do the same.

As Mr. I.B. Chialo, Acting Ambassador for Tanzania when I was in China, explained to me, the ideologies of the two countries have for long had their similarities and historically Tanzania has followed China in many ways. He felt that there was much to be learnt from China even today and pointed out that, at the time we were speaking, President Mwinyi was welcoming to Tanzania a delegation (later I learnt that it was the first visit to Africa of delegates of the organisation of such a high level of representation) from the China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC) which can claim credit for the remarkable development of foreign joint enterprise and other investment now to be seen in China. The Daily News in Tanzania later quoted President Mwinyi as having asked the delegation to share with Tanzania some of China’s experience in dealing with foreign investors in a socialist state. And just as in Tanzania there are those in China who are saying that the changes must be halted as they are endangering the national policy of socialism and its objective of achieving equality amongst people. Mr Chialo also told me that, although. because of the warmth of the relations between the two countries, Tanzania still received favours, the ‘era of mutual admiration is over’. “We are learning to be tough in negotiation from them” he said. He quoted several potential joint projects in Tanzania being held up because of the severe conditions on which the Chinese were now insisting.

After a busy month my visit came to an end. The Ministry of Railways let it be known that it would not be possible for me to talk to any of the persons who had contributed to the great railway project. The Chinese bureaucracy is still there.

David Brewin