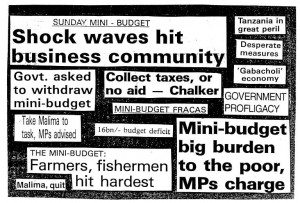

Finance Minister Professor Kighoma Malima shocked Tanzanians on January 2nd 1994 when he announced a series of drastic measures in a mini-budget designed to balance government income and expenditure and deal with a serious shortfall in revenue. He proposed to cut expenditure by no less than 40%.

In the following article Roger Carter explains the background to the financial crisis and the measures the government is taking.

LONG TERM INTERESTS AND SHORT TERM NECESSITIES

In common with other Countries at a similar stage in development, Tanzania is faced by a continuing conflict between important long term interests and urgent short term necessities. There can be little doubt that the expansion and enrichment of primary education and the extension of primary health care are among the prerequisites of rapid economic growth. The road and rail systems need radical improvement, the telephone network to be more reliable and responsive. Much capital investment of this kind, for example on schools, health centres, or roads, brings in its train new charges on the recurrent budget for the purposes of operation and maintenance. But it is these costly services that are being starved of resources on account of the pressing need to balance the budget and to bring down inflation.

CONTROLLING INFLATION

Inflation has immensely damaging consequences. As wage increases lag behind price rises, inflation impoverishes the wage earning section of the population and may well cause social unrest. As an indicator of the government’s inability to fund its expenditure out of revenue, inflation undermines investor confidence both at home and abroad. Inflation introduces uncertainties into all forward planning and complicates the task of exporters. As inflation means that the value of the currency is falling, bank balances and contracts denominated in local currency lose some of their value and saving is discouraged.

The importance of controlling inflation has been acknowledged in successive budgets. One major cause of inflation has been the willingness of the government and the National Bank of Commerce to finance the deficits of lossmaking parastatals, notwithstanding warnings by the government that the practice must end. Having no idle surpluses, the government and the Bank have been obliged to rely on inflationary measures involving the creation of new money to meet this need. There are of course circumstances in which a parastatal is providing an essential service and cannot be replaced in the short run. In the case of some crop parastatals the first step has been to remove their monopoly powers and to expose them to competition. Survival then depends on the ability of these parastatals so to reorganise themselves as to operate efficiently without government subventions. The government has set up a Parastatal Sector Reform Commission to advise on the future of parastatals generally, whether by reorganisation as joint venture companies, outright sale to the private sector, or in some cases liquidation. In this matter the government is guided by the intention in the medium term to divest itself of direct responsibility from all productive enterprises.

THE SHORTFALL IN REVENUE

The immediate goal, then, is to end support for loss-making concerns and to balance the budget without resort to borrowing from the Bank, or other inflationary devices. Unhappily, this aim has received a setback with the discovery for the second year running of a serious shortfall in revenue, notwithstanding measures announced in the budget speech to enhance collection and improve motivation among collectors. It was estimated that income by the end of the financial year on 30th June would be some 12% short of the budget figure of Shs. 235.6 billion. Expenditure was also running ahead of estimates. A major cause of the shortfall in revenue is believed to have been inadequate collection of customs duties and steps have been taken to ensure strict adherence to the customs tariff and to put an end to illegal import practices. Increases in customs duties on commodities otherwise produced locally were announced and a 10% duty on industrial raw material, lifted in the budget, was reimposed. On the expenditure side, a decision to undertake the phased closure of 12 embassies and to begin the process by a reduction of home-based and local staff was announced. Foreign visits by government officers funded by government and all transfers of civil servants were suspended. Departmental accounting officers were to see that budget provision was not exceeded; cheques and warrants not covered by balances into the Paymaster General’s account would not be honoured.

The government hopes that these measures will restore revenue collection to the level foreshadowed in the budget without significant damage to current economic reforms. Understandably the reaction of the trading community was one of shock. Some of the increases in duties, such as those on drugs from 10% to 40%, were seen as favouring the rich, while the proposed 10% duty on industrial raw materials was a setback for the domestic economy. Representatives of the Confederation of Tanzanian Industries and of the opposition party CHADEMA led by Mr. Edwin Mtei, the former Governor of the Bank of Tanzania, took the view that the budgeted revenue target would be reached if adequate steps were taken to deal with tax evasion and corruption. The government’s proposals met with a hostile reception in Parliament. Summing up for the government the Minister for Finance announced reductions in the rates of duty previously announced. Imported drugs were now to face an import duty of 15%, while duties on raw materials used for the local manufacture of medical and veterinary drugs were to be limited to 5%.

Any substantial increase in rates of duty must have two adverse consequences for the economy. First, it is likely to create difficulties for industrial concerns already experiencing cash flow problems, with a risk of insolvency in some cases. Secondly and more importantly, by increasing costs it will tend to put up the rate of inflation and in this way to frustrate a primary object of government policy. The government is aware that morale in the public service is just as important as fiscal changes. Rewards in the public service are now much too low as a result of the decline in the value of the currency and the result has been a tendency towards poor performance, absenteeism, and unpunctuality in an environment offering temptations for corruption, while overstaffing has created a financial burden well beyond the government’s means. It is planned to reduce the size of the service during the current financial year by 20,000 civil servants, taking advantage of the progressive reduction of government responsibilities in the productive sector. It is expected that it will be possible to create a more adequate salary structure when the public service has been reduced to a more sustainable size.

NOT ALL GLOOM

In spite of these problems Tanzania has been able to record some notable achievements. The administration of foreign exchange under the supervision of the Bank of Tanzania is going well. The rehabilitation of the road network is proceeding with energy. As a recent World Bank report shows, agricultural production has been increasing at an average annual growth rate of 5.3% between the years 1987 and 1991. Associated with this rate of growth has been an 8.3% real increase in producer prices between 1981-83 and 1989-91, followed by further increases in subsequent years. The ending of the marketing monopoly of the National Milling Corporation has given farmers direct or indirect access to local markets and cash on the nail instead of the long, discouraging delays in payment that previously often prevailed. An important consequence of the rise in rewards for agricultural producers has been a wider dispersal of the proceeds of production among the population in general.

So in spite of immediate problems all is not gloom. But the revenue crisis has once again illustrated the immense difficulties faced by a country at Tanzania’s stage of development in undertaking the capital and recurrent financing of vital infrastructure and services in the face of immediate demands on resources. Such crises can arise in a variety of ways. In the previous financial year, the government was obliged to resort to inflationary borrowing, as drought had undermined the electricity supply at Kidatu dam, bringing industry repeatedly to a standstill over a period of several months and seriously interfering with tax revenues. Before that, serious floods in the Lushoto and Korogwe areas forced the government to make provision for emergency relief. Over all of these unexpected demands on resources hang the increasing needs of a population estimated to be growing at about 3% per annum.

As successive finance ministers have shown, balancing the budget comes high in their lists of priorities. Some of the measures needed to be taken, such as the reduction in the size of the civil service, are inevitably unpopular. But it is clear from the budget speech and its endorsement by Parliament that the nettle has been grasped and that a fall in inflation, bringing with it important benefits both to the economy and the population in general, could now be a realistic expectation.

J Roger Carter

DAMAGE TO SCHOOLS

As a reflection of the financial situation some schoolchildren have been protesting violently about the ‘bad food’ being provided in schools – Uqali and beans every day. Ifakara secondary school students have set fire to school buildings and have caused Shs 6 million damage. Kwiru school had to be closed after serious vandalism and 46 students at Arusha school were suspended after unrest in the school.

Pingback: Tanzanian Affairs » BALANCING THE BOOKS