Edited by John Cooper-Poole

THE WAYS OF THE TRIBE – A CULTURAL JOURNEY ACROSS NORTH-EASTERN TANZANIA, by Gervase Tatah Mlola, published by E & D Vision Publishing, Tanzania, October 2010. www.edvisionpublishing. co.tz. ISBN 978 9987 521 42 5. The book is available at all outlets of Novel Idea Bookshop in Tanzania, Kase Book Stores in Arusha, and the offices of Park East Africa Ltd., and the Tanzania Cultural Tourism Programme. In the UK, the book will shortly be available from www.africanbookscollective.com for £20.95 See www.waysofthetribe.com for more information on the book and some sample pages.

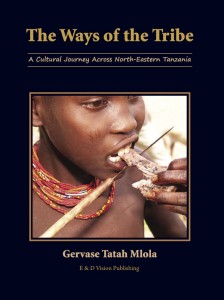

Tanzania has a rich and diverse cultural landscape. The Ways of the Tribe is a compelling and authoritative reference work that makes a valuable contribution towards documenting the ancient heritage of the various tribes that populate this vast and beautiful land. Mlola’s first book offers readers a fabulous survey of fourteen tribes from the north-east of Tanzania.

Whilst the Maasai may be familiar to readers worldwide, the book also chronicles less familiar peoples like the Barabaig of Hanang District and the Mbugu of the Usambara mountains. This account is the result of a decade of research arising from visits to the present-day tribal communities by the author – a respected travel writer and cultural expert.

The content of this book is arranged by tribe and within each chapter there are sections on origins, history, community life, and customs. The contribution of each tribe to the national life and development of the nation is also included with a range of fascinating stories, such as the heroic story of the Olympic runner John Stephen Akhwari of the Iraqw.

The Ways of the Tribe is a lively and engaging chronicle packed with legends, humour, and colourful insights into everything from the naming of babies to the brewing of sugar cane beer. Each chapter also contains a very useful bibliographical section; the work would benefit further from the inclusion of an index. In addition to many striking images contributed by Colin Hastings (now a director at Majority World Photo Library) and photographer Briony Campbell, there are also illustrations by artists Abdul Gugu and Bosco Mpitivyako. Their work (together with a selection of maps) contributes to the bright and attractive appearance of this publication.

Mlola’s scholarship has resulted in a very accurate historical account, but his work also provides another level of understanding beyond the factual. The author’s first-hand experiences, passion, and dedicated research also offer readers a valuable understanding of the interplay between the beauty of the land and the beauty of the people. In doing so he offers a unique insight into the essence of the identity and vibrancy of these peoples.

In addition, the author provides a description of the present-day circumstances and lifeways of these peoples. In doing so, we are reminded these tribes are real communities whose rich heritage is sadly threatened by a host of issues often faced by indigenous peoples around the globe who strive to retain their identities in a rapidly changing world. The final chapter on the “lost tribe” of Engaruka is a reminder of the fate of indigenous groups who are unable to withstand the social, economic and environmental pressures that may come to threaten their future.

The Ways of the Tribe is a well-presented and important reference work that will have widespread appeal. For students and scholars it is a valuable historical chronicle and present-day commentary on the tribes under discussion. The book should give Tanzanians a greater appreciation of their diverse and lively heritage. Tourists planning a visit to the region that is home to many worldfamous destinations will greatly benefit from understanding the peoples they may encounter on their holidays. And finally for the general reader, this lively reference work is a wonderful way to begin exploring the people, places and cultures of this fascinating part of Africa.

Antony Shaw.

This review first appeared in Tantravel, the official travel magazine of Tanzania Tourist Board, and we are grateful for permission to re-publish it here.

MAJI MAJI. LIFTING THE FOG OF WAR James Giblin and Jamie Monson, eds., Brill, Leiden, pp.xii and 325, 2010, ISBN 978 90 04 18342 1. US$107, Eur 75.

The greatest achievement of the first ‘Dar es Salaam school’ of history in the 1960s was the Maji Maji research project. Over forty years ago there was money available for student research in the vacations and very many were deployed to collect oral testimony in the areas which had been affected by Maji Maji. This research produced what Giblin and Monson call ‘the foundational accounts’ of the rebellion, mainly by John Iliffe and the late Gilbert Gwassa, in collections of ‘records’, articles, and books. These now classic works were very popular and influential both inside and outside Tanzania. For decades it did not seem necessary, or perhaps even possible, to review and revise them.

Forty years later, though, so much new work has been done on central and southern Tanzania that a second Maji Maji research project has become possible and perhaps essential. A ‘multi-year collaborative project … began in 2001’ and has taken longer and cost much more than the original research. This book is the result. Though its contributors present a variety of interpretations of Maji Maji it is in essence a revisionist work. The 1960s account of the rebellion, the editors hold, was unduly ‘statist’. It overestimated the reach and the presence of the colonial state and it overestimated the proto-nationalist intentions of resistance to it. It was also too tidy, making the violence seem more co-ordinated than it really was. It laid too much stress on the spread and effect of the maji medicine but at the same time accepted too uncritically the existence of ‘tribes’. The real situation was much messier and more shaped by local and fragmented realities.

Reading this book reminded me of the famous story of the blind men and the elephant – one feeling its tail and deducing it must be a snake, another embracing a leg and deducing it must be a tree and so forth. The contributors find in Maji Maji what they most hope to find. Thaddeus Sunseri, who has done so much good work on environmental history, says that ‘Maji Maji was a symbolic clash of hunting cultures’ – it was ‘the war of the hunters’. (119) Lorne Larson, who has been working on the Ngindo for decades and who has written on witchcraft eradication movements, finds Maji Maji to be the climax of the politics of medicine. Heike Schmidt, who has an active interest in black female political power, lays stress on the role of Nkomanile, an Ngoni ‘royal woman’. (197) James Giblin, who has ‘domesticated’ rural Tanzanian politics, emphasises an oral tradition that ‘the war occurred here [in Ubena] because of a woman. Mpangire wanted to marry Mwangasama, for the very reason that Mpangire had a great desire for brown women’. (284) Giblin finds this story ‘as plausible and as faithful to our admitedly incomplete knowledge of the events of September 1905 as any account yet devised by historians’. (286) In fact, Maji Maji was all these things and more, just as an elephant has ears and a tusk as well as a tail and legs.

Maji Maji was about the contest over elephants and it was about how to resolve the problem of evil. It was about desire, gender and slavery. It was about the failures of chiefs and elders as well as about the presumptions of German colonial officers. It was a revolt against colonialism but it was something much more profound than that. It was an attempt to resolve the desperate problems of society, economy, belief and enviroment. The brutality of its repression foreclosed any possibility of reaching solutions. As Heike Schmidt writes: ‘Death, starvation, displacement, enslavement, forced labour and humiliation dominated life into the years following the fighting … The deadly silence observed in 1907 still resonates in Ungoni today.’ (218-219).

This collection makes many innovations. There is a terrifying chapter by Michell Moyde on the Askari, which makes great play with John Iliffe’s work on honour. Heike Schmidt’s historian’s chapter on Ungoni is balanced by a chapter on the archaeology of Maji Maji in the district by Bertram Mapunda. Very effective use is made of German missionary records, both Catholic and Protestant – though there is little on the role of African Christians. The book is beautifully produced and illustrated. It is a pity that it is too expensive to be bought by the average reader. It is possible that even if many Tanzanians read it they would not be as excited as a preceding generation was by the ‘statist’ accounts of forty years ago. Complexity is hard to digest or to teach. But anyone interested in Tanzanian history should obtain and read this book.

Terence Ranger

CHECHE: REMINISCENCES OF A RADICAL MAGAZINE edited by Karim Hirji, Mkuki na Nyota 2010. ISBN 978 9987 08 098 4.

THE COURAGE FOR CHANGE: RE-ENGINEERING THE UNIVERSITY OF DAR ES SALAAM by Matthew Luhanga, Dar es Salaam University Press 2009. ISBN 978 9976 60 479 5. £22.95. Both books available from African Books Collective, P.O. Box 721, Oxford OX1 9EN www. africanbookscollective.com

Two recent books, one edited by Karim Hirji, the other by former Vice Chancellor Matthew Luhanga, contribute to the historiography of the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM), an institution which has seen significant and rapid changes in its relatively short history.

Karim Hirji opens his chapter, entitled “The Spark is Kindled,” with a vivid description of a Friday evening at UDSM in 1969. “Only a handful of staff offices are lit. Walter Rodney types out page after page of How Europe Underdeveloped Africa…” (p. 18). He goes on to describe an animated meeting of the University Students African Revolutionary Front (USARF), the radical socialist student group that founded Cheche, a short-lived but fiery student magazine published from 1969 to 1970. At this meeting a young radical named Yoweri Musevani speaks to the crowd; Issa Shivji and others who will become prominent Tanzanian intellectuals are there. In his description Hirji captures the spirit and enthusiasm of these activist students and provides a rich picture of UDSM’s vibrant intellectual atmosphere in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Likewise, Matthew Luhanga’s recounting of his time as UDSM’s Vice-Chancellor in The Courage for Change includes vivid, and often humorous, descriptions of significant events that took place during his tenure from 1991-2006. Indeed, the core contribution of both of these works is the detailed personal narratives and recollections of two significant, yet very different time periods in the history of UDSM.

Cheche recounts an intellectually vibrant period of UDSM’s history, the late 1960s and early 1970s, just after the Arusha Declaration, when students and scholars were engaged in building a university relevant to the socialist development of Tanzania. The volume, edited by Hirji, one of the founders of USARF and Cheche, can be divided into two parts. First, the core of the book gives Hirji’s account of the rapid rise and fall of the radical socialist student group and it’s associated publication. It includes reminiscences of other USARF members, such as Henry Mapolu, Zakia Meghji, George Hajivayanis, and Christopher Liunda about their work with Cheche and its successor publication, Maji Maji. Hirji has even included an article by a young Yoweri Musevani that appeared in a 1970 issue of the magazine. This section ends with a selection of poems, some republished from Cheche, that express the socialist ideals of USARF and its members. The second section bookends this core narrative of personal recollections. In the first and last three chapters, Hirji provides his socio-historic analysis of the wider national and global context in which the authors of the book were steeped. Utilizing personal observations and drawing on the work of a wide range of scholars, Hirji offers an analysis of why socialism failed in Tanzania (or was never truly enacted) and his critique of the capitalist imperialist system. The final chapter contains his reflections on the contributions and the deficiencies of USARF and Cheche. He ends the book with a call to the next generation to take up the cause of African liberation. While Hirji’s call to arms is inspiring and his socialist historical analysis is detailed, albeit unapologetically agenda-driven, it is the rich and detailed story that he and others tell of their personal experiences with USARF, Cheche, and the socialist era at UDSM that make a solid contribution to the historiography of the University of Dar es Salaam and Tanzanian intellectuals.

Luhanga’s Courage for Change focuses on another key time in the history of the university. In 1991, when Luhanga began his tenure as Vice Chancellor, the university was reeling from extreme economic hardship of the 1980s. Luhanga tells the story of his implementation of the Institutional Transformation Programme and UDSM’s subsequent slow emergence from a period of significant decline. Throughout the text Luhanga provides numerous facts and figures, supporting his contribution to UDSM’s recovery. These are also available in his previous publications (Strategic Planning and Higher Education Management in Africa, 2003 and Higher Education Reforms in Africa, 2003). While these tables, bullet points and statistics give some context, they are repeated from other sources and give a rather flat picture of UDSM’s recent history. It is the stories that Luhanga weaves amongst these facts of his hasty appointment, student protests, a “kidnapping”, economic hardships, and conflicts between the Hill (UDSM) and the Tanzanian government that are of interest. Of course, Luhanga’s account comes from the political perspective of the highest level of university administration, contrasting sharply with Hirji et al.’s narrative from radical students’ perspectives. Both are necessary, however, to gain a fuller picture of the rich history of the University of Dar es Salaam.

Amy Jamison

FROM BONGOLAND TO DAR ES SALAAM; URBAN MUTATIONS IN TANZANIA, co-ordinated by Bernard Calas, originally published in French by Karthala of Paris around 2006, now translated by Naomi Morgan, and published in English by Mkuki wa Nyoka Publishers Ltd in association with the French Institute for Research in Africa, pp 417, ISBN 978-9987-08-094-6. Available from African Books Collective, P.O. Box 721, Oxford OX1 9EN. www.africanbookscollective.com. £34.95.

This book brings together in English a dozen papers by a group of French academics in the fields of geography, economics, political science, sociology and history, Their research, done between 1996 and 2002, covers Dar es Salaam’s foundation and exponential growth, the harbour, trade and commerce, local government (and its shameful neglect in the 1970s), land and planning controls, slum life, public and private transport, primary education, and water supply. There are also chapters on the impact of various ethnic groups and the colonisers on the metropolis’ culture and society; and finally a dissertation on the city’s relations with Zanzibar.

On all these matters, this volume offers useful data and informed judgements (on, for example, the problems of Ujamaa and the subsequent Structural adjustment Programme). It also provides numerous insights into the life of the city’s inhabitants over the years. As such, it will be a useful quarry for future students of urban development in sub-Saharan Africa, as well as of the story of Dar es Salaam.

The book has severe limitations however. There is no index; and because few of the writers knew Swahili, their work lacks the immediacy of oral testimony, while the bibliography is inevitably mostly of works in French. Moreover, the chapters vary in quality; some are clear and direct, others are prolix and complex. Some are a pleasure to read; others very heavy. The translator tackled her job gallantly but appears to have had fearful difficulty at times in turning academic French into straightforward English. My review copy had not been proof-read, and contained frequent irritating howlers – like “Babamoyo” on page 12 – as well as the omission of illustrations and repetition of sentences in several places.

Unless a clean and much tidier edition is published, this is a poor example of the work of the publishers, Mkuki wa Nyoka. Despite all these drawbacks however, we may be grateful to the authors, coordinator and translator for contributing another useful building block in Tanzania’s recent history.

Dick Eberlie

SPEAK SWAHILI, DAMMIT! by James Penhaligon. Authorhouse U.K. Ltd. 500 Avebury Boulevard, Central Milton Keynes, MK9 2BE. www.authorhouse. co.uk. ISBN 978 1 4490 2373 7. Speak swahili Dammit, is available via the author’s book website, www.SpeakSwahiliDammit.com at “just over £10”.

For those Wazungu who lived in East Africa from the Fifties onwards, this book will bring back many fond memories. It was good to hear a tale from someone who was brought up in what was then Tanganyika later to become Tanzania, as to my knowledge there are few other similar accounts.

James Penhaligon was raised in the bush in a remote area near Mwanza next to Lake Victoria at the Geita gold mine and after the premature death of his father, his mother and sister carried on living in the area with his mother working to make ends meet. The young “Jimu” soon comes under the spell of Africa and one can see the enthusiasm he has for the country, people and especially the language.

Apart from Jimu’s adventures, the book also gives the reader a little history about Tanzania when he meets an old soldier from Von Lettow Vorbeck’s Deutsch Ost Africa Corps and about the campaigns of the First World War which I remembered being spoken about when a pupil at Lushoto in the Sixties. Jimu’s story continues with his education at Arusha and Nairobi, and I can identify with the black and blue bruises that he describes! The Swahili interspersed throughout the book was interesting to a Swahili speaker although there was quite a lot of repetition of phrases that sometimes detracted from what is a really a cracking tale that has tragedy, adventure and humour in jembefuls (spadefuls).The book was also a little long but overall an enjoyable read and brought back wonderful memories of Tanzania.

David Holton

Dick Eberlie was District Officer in Dar es Salaam, Kisarawe and Morogoro and subsequently worked for the Tanzania Tea Grower’s Association. He was Secretary of the Tanzania Society for the Blind and a member of the Editorial Board of the Tanzania Notes and Records. Author of “The German Achievement in East Africa”, he is now an adviser on industrial organisation and business representation with the British Executive Service Overseas (BESO).

Contributors

David Holton was educated at Lushoto Prep School before returning to school in England. He has been manager of Bookland in Chester and a regular book reviewer for BBC local radio.

Amy Jamison holds a PhD in Educational Policy from Michigan State University, and conducted her doctoral research on the history of the University of Dar es Salaam. She is currently the Assistant Director of the Center for Gender in Global Context and continues to pursue research focused on African higher education.

Terence Ranger was the first Professor of History at University College, DSM, 1963-1969. He is currently Emeritus Professor at the University of Oxford and has been a member of the Britain-Tanzania Society for thirty years.

Anthony Shaw is Managing Director of Creo Communications, a Tanzania-based company offering communication consultancy and English language support services to individuals, organisations and businesses.

Pingback: Conflict and Consensus in Constitution-making in Tanzania – 20th April 2016 | Britain Tanzania Society