by Ben Taylor

On 8 August 1914, the Royal Navy bombarded the German wireless relay station in Dar es Salaam. War had broken out in Europe just days earlier, and already it had come to East Africa.

In the shadow of the horrors of western Europe, space in the popular memory for the East African theatre of the First World War is limited. Such room as there is tends to be dominated by Boys’ Own tales of derring-do, successes against the odds and heroic failures.

The madcap British scheme to gain naval supremacy on Lake Tanganyika is Exhibit A. Two 40 foot motorboats, HMS Mimi and HMS Toutou, were shipped out to South Africa and transported 3,000 miles by land (including being dragged for 146 miles through the jungle of the Belgian Congo) to reach the lake. It should never have succeeded, and yet it did, capturing one German vessel and sinking another before forcing the Germans to scuttle their 220-foot flagship Graf von Götzen (now the MV Liemba).

This inspired C.S. Forrester’s novel, The African Queen, a film of the same name starring Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn, and, more recently, Giles Foden’s book Mimi and Toutou Go Forth. Partly as a result, though the military significance of the Battle of Lake Tanganyika was negligible, the story became arguably the most well-known episode of the Great War in East Africa.

Or perhaps that accolade should go to the sinking of the German battle-cruiser SMS Konigsberg. Just before outbreak of war, the ship had given the British navy the slip from Dar es Salaam harbour. She frustrated the British in the Indian Ocean for well over a year, sinking ships including City of Winchester and HMS Pegasus, before eventually being cornered and sunk in the Rufiji Delta.

The Germans began the war with a well-trained force of some 5,000 men under the leadership of Lieutenant Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. They launched an early attack over the border into British East Africa (now Kenya) to disrupt the Mombasa-Nairobi railway, capturing an area around Taveta and Tsavo. This was the only British territory anywhere worldwide to be occupied during the entire First World War. During one skirmish, a German sniper is said to have hidden inside a hollow baobab tree; locals still claim the tree to be “the most shot at tree during World War I.”

In November 1914, a British/ Indian Expeditionary Force launched a disastrous attack on the port of Tanga, the terminus of the strategically important Usambara railway to Moshi. There was an agreement that guaranteed the neutrality of Tanga, so the British gave the Germans 24-hours’ notice that the agreement was cancelled. Lettow-Vorbeck thus had time to bring reinforcements down the line from Moshi. When allied troops were landed, they struggled against a swarm of bees. The Germans faced similar problems, but they prevailed in what inevitably became known as the “Battle of the Bees”.

Guerrilla tactics and impossible logistics

These episodes have a place in the history of the Great War in East Africa. But they do not tell the full story – far from it – for this was a brutal war.

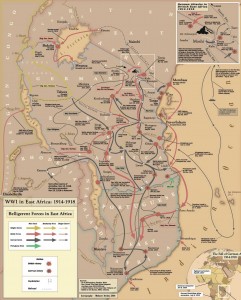

In contrast to the immobile trench warfare in western Europe, the war in East Africa was one of mobility and guerrilla tactics: brief battles and long marches. The allied troops launched an offensive in early 1916, after which Lettow-Vorbeck conducted a guerrilla war for two and a half years around the south of German East Africa (Tanzania), the northern part of Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) and finally in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia).

Lettow-Vorbeck by 1916 had around 20,000 troops – mostly Africans with German officers – while the allied combatants numbered around 150,000, under the command of South African General Jan Smuts. Smuts’ troops were drawn from Britain, the British colonies in East, West and Central Africa, South Africa, India and the Belgian Congo. By the end of the war, the allied force was almost entirely African.

Troops and carriers would often walk twenty miles a day, every day for a month, exposed to tropical weather of intense heat and drenching rain. Two King’s African Rifles battalions marched 1,600 miles in seven months, in the process fording 29 large rivers and fighting 32 engagements. Much of this was done with virtually no rations, subsisting on what could be found locally. Disease killed more British troops than combat. On returning from the field, soldiers were described as “resembling the victims of famine.”

In the words of one South African quartermaster, the war “involved having to fight nature in a mood that very few have experienced and will scarcely believe.” Another stated that “there is no form of warfare that requires so much inherent pluck in the individual as bush fighting.” And an officer who had fought on the Western Front wrote: “what wouldn’t one give for the food alone in France, for the clothing and equipment, and for the climate, wet or fine”.

A Malawian veteran described the experience: “Think of lying on the ground where the hot sun is beating directly on your back; think of yourself buried in a hole with only your head and hands outside, holding a gun. Imagine yourself facing this situation for seven days, no food, no water, yet you don’t feel hungry; only death smelling all over the place. Listen to the sound from exploding bombs and machine guns, smoke all over and the vegetation burnt and of course deforested. Look at your relatives getting killed, crying and finally dead. These things we did, experienced and saw.” (Page, cited by Samson).

Supply chains for food, medicines and munitions were impossible to maintain. Historian Edward Paice describes the logistical challenge: “As the availability of livestock for transport proved incapable by mid1916 of matching the depredations of disease, the onus fell on the only alternative – human porterage. The mathematics are sobering. … 16,500 carriers were required to transport a single ton of supplies – enough to feed 1,000 askaris and their camp-followers for one day – for the simple reason that 14,000 of them were needed to carry food for the column while 2,500 carried the food for the troops. … The troops required more than a million carriers to keep them in the field.”

The German troops largely abandoned efforts to maintain a supply chain, and instead appropriated crops and livestock without payment. They recruited some 300,000 carriers, again largely without payment.

The effect of all this on the civilian population was devastating. Agriculture became more and more difficult, leading, by 1917-18 to famine in much of East Africa.

And for what?

M’Inoti wa Tirikamu, a carrier from Meru, “wondered why white men hate each other so much. They looked so much like brothers. We asked ourselves: Do they fight for land, or for the power to rule, or is it because they are all white, or why?”

Odandayo Mukhenye Agweli, an askari of the King’s African Rifles had similar thoughts: “To this day, I still do not know why we fought the Germans and how the war began. Though we admired the European ways of fighting, we were still left wondering why so many people had to die. In our tribal wars, the number of the dead was never very big.”

There is no answer to these questions that can possibly justify the war. Lettow-Vorbeck saw the role of his army as a drain on allied resources – drawing men and weaponry away from more important battles in Europe. Though he evaded capture until the war had ended, at which point he surrendered in Northern Rhodesia, he never really drew significant manpower away from Europe. The allies fought the war mostly with African soldiers.

Historian Edward Paice sees the war in East Africa as “the final phase of the Scramble for Africa”, which “epitomised the vainglorious imperial ambitions which helped to trigger – and certainly prolonged – World War I”. The British gained a League of Nations Mandate over Tanganyika and the Belgians gained one for Rwanda and Burundi. But the war laid bare the human vulnerability of the white man as never before, and sowed seeds of a demand for independence. The First Pan-African Congress was held in Paris in 1919, to coincide with the Versailles Peace Conference. It called for Africa to be granted home rule, and for Africans to take part in governing their countries as fast as their development permits.

The real cost

In contrast to the (relative) glamour of a small British navy expeditionary force on Lake Tanganyika, the real story of the war in East Africa is far more brutal. The vast majority of war deaths were among carrier units – an estimated 95,000 on the allied side, probably well over 50,000 among the German carriers. Around one in eight of the adult male population of British East Africa – today’s Kenya – lost their lives either as askaris or carriers. And an estimated 300,000 civilians in German East Africa died as a direct result of the war and the 1917-18 famine. The official death toll among British combatant and support units was over 105,000 men. This equalled the number of American war deaths, and was almost double the numbers of Australian, Canadian or Indian troops who lost their lives during the war.

Disgracefully, however, the official death toll does not include carriers. According to Paice: “There were many British combatants in East Africa who paid tribute to the carriers on whom they were utterly dependent for survival … But when the mortality rate became common knowledge in Whitehall it was deemed a “bloody tale” best ignored, or even suppressed, as Britain sought colonial prizes in Africa at the Paris Peace Conference. As one colonial official put it, in particularly arresting terms: the conduct of the campaign “only stopped short of a scandal because the people who suffered the most were the carriers – and after all, who cares about native carriers?””

And yet, somehow, the worst was still to come. In September 1918, as the war was coming to an end, Spanish Flu reached sub-Saharan Africa. In British East Africa, probably as many as 200,000 died, nearly 10% of the total population of the country. In German East Africa, the death toll from Spanish Flu may have been as high as 20% of the population. “There came a darkness” is a much-repeated phrase in oral histories of the time. This was a war with an immense human cost: on the troops and on the carriers, and most of all, on the civilians.

Sources

Great War in Africa Association http://gweaa.com/

Edward Paice – How the Great War razed East Africa, Africa Research Institute http://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/publications/counterpoints/how-the-great-war-razed-east-africa/

Edward Paice – The Great War and the size of the butcher’s bill, The Africa Report

http://www.theafricareport.com/Columns/the-great-war-and-the-size-of-the-butchers-bill.html

Anne Samson – When two bulls fight

http://thesamsonsedhistorian.files.wordpress.com/2014/07/when-two-bulls-fight.pdf

Anne Samson – The numbers game: how many men fought in Africa?

http://thesamsonsedhistorian.wordpress.com/2014/06/13/the-numbers-game-how-many-men-fought-in-africa/

Wolfgang H Thome – Battlefield East Africa, 98 years and counting http://wolfganghthome.wordpress.com/2012/06/24/battlefield-east-africa/

World War I in Africa: What happened in Africa should not stay in Africa http://wwiafrica.tumblr.com/

Wikipedia – East African Campaign (World War I) https://en.wikipedia.org/ wiki/East_African_Campaign_(World_War_I)

Wikipedia – Battle for Lake Tanganyika https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_ for_Lake_Tanganyika

Wikipedia – Battle of Tanga https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Tanga

Wikipedia – Schutztruppe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schutztruppe