by Ben Taylor

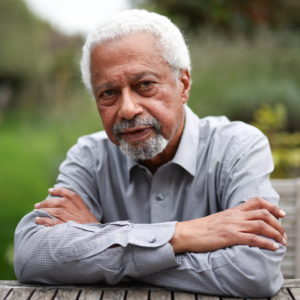

Abdulrazakh Gurnah wins Nobel Prize for Literature

The Zanzibar-born, British-based author, Abdulrazakh Gurnah, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in October 2021. His win was a surprise to many – he did not feature among the 42 names listed by one bookie on the morning of the announcement.

In making the award, the Nobel committee explained its decision as reflecting “his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.”

Best known for his novels including Paradise (1994), which was shortlisted for both the Booker and the Whitbread Prize, Desertion (2005), By the Sea (2001) and Afterlives (2020), Gurnah’s work has regularly foregrounded characters more usually found on the sidelines of mainstream storytelling. His writing explores themes of loss, alienation, migration and subjugation, often in historical colonial settings, with Zanzibar and the East African coast prominent.

Born in Zanzibar in 1948, Gurnah left Tanzania as a teenager following the 1964 Zanzibar revolution, and has lived in the UK ever since. He is Emeritus Professor of English and Postcolonial Literatures at the University of Kent.

In Tanzania, Gurnah’s Nobel Prize win sparked both joy and debate. Many Tanzanians acknowledged the recognition of Abdulrazak Gurnah’s work, while others questioned whether they can honestly claim the author as their own.

Both the presidents of Tanzania and semi-autonomous Zanzibar were swift in hailing Gurnah’s achievement. “The prize is an honour to you, our Tanzanian nation and Africa in general,” Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan tweeted. Zanzibar leader Hussein Ali Mwinyi said, “We fondly recognise your writings that are centred on discourses related to colonialism. Such landmarks, bring honour not only to us but to all humankind.”

The prize reignited politically charged debates around the relationship between Zanzibar and mainland Tanzania, as well as around citizenship and identity in the modern world.

“One of the reasons Tanzania can’t allow dual citizenship is the fear that Abdulrazak Gurnah and his grandparents, who fled Zanzibar to escape the persecution of Arabs during the Zanzibar Revolution, would return and claim their stolen assets. And we’re shamelessly celebrating his victory?” wrote Erick Kabendera, a journalist.

“The debate about the “Tanzanian” identity of Abdulrazak Gurnah should be an awakening call, a trigger to our government to think about justice, dual citizenship, union matters and quality education and teaching – how do we do in writing and literature?” tweeted social scientist Aikande Kwayu.

“Gurnah identifies himself as Tanzanian of Zanzibar origin. Living in diaspora, having been exiled or even feeling dislocated from his country does not take away his heritage and identity. That is part of who he is,” said Ida Hadjivayanis, lecturer of Swahili studies at School of Oriental and African Studies in London. “There are so many people living in diaspora with children whose nationalities are foreign but who identify as Tanzanian – and so that is the homeland.”

Gurnah himself told journalists his connections to Tanzania remain strong. “I go there when I can. I’m still connected there … I am from there. In my mind I live there.”

In his acceptance lecture, Gurnah spoke of his motivation in writing, and the purpose of writing in society. “Writing is not about one thing,” he said, “not about this issue or that, or this concern or another, and since its concern is human life in one way or another, sooner or later cruelty and love and weakness become its subject.”

“I believe that writing also has to show what can be otherwise, what it is that the hard domineering eye cannot see, what makes people, apparently small in stature, feel assured in themselves regardless of the disdain of others. So I found it necessary to write about that as well, and to do so truthfully, so that both the ugliness and the virtue come through, and the human being appears out of the simplification and stereotype. When that works, a kind of beauty comes out of it.”