by Martin Walsh

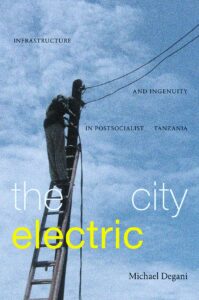

THE CITY ELECTRIC: INFRASTRUCTURE AND INGENUITY IN POSTSOCIALIST TANZANIA. Michael Degani. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina, 2022. xii + 254 pp. ISBN: 9781478023777 (ebook free to download from https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/58921 ; also available for purchase as a hardback and paperback).

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of electricity and its presence and absence in a developing economy like Tanzania’s. Stories about its generation and supply and the controversies surrounding them feature regularly in the national and international media, including the ‘Energy and Minerals’ pages of Tanzanian Affairs. Whether or not they are aware of all the shenanigans that are alleged, ordinary citizens experience their consequences viscerally, not least where electricity is yet to be supplied by TANESCO (the Tanzania Electricity Supply Company), or when that supply is cut. Many readers of this review will not need to be reminded what it is like sweating in the humidity of a fan-less night or pretending to ignore the throbbing of the generator that is keeping their lights on and food refrigerated. Some will be all too familiar with the hustling and haggling required to secure or restore a connection; others will have suffered the anxiety that comes from having to complain again and again about inflated bills, a recurring nightmare for householders without prepaid meters and often for tenants sharing one.

And yet, somehow or other, everything kind of works, notwithstanding the pace of economic and demographic growth and the constant demand for more electricity. Mike Degani’s well-crafted anthropological study, The City Electric, goes a long way towards explaining why and how all things TANESCO don’t completely fall apart, both at national level and from the perspective of the parastatal provider and its everyday consumers in Dar es Salaam. As its subtitle suggests, it also takes its place alongside other recent studies that tell us what has happened more generally in the often-troubled transition of Tanzania from state socialism to its present condition, however that might be characterised. It’s not the neat development trajectory that modernisers and then neoliberal reformers envisaged, but an at times messy bricolage that has incorporated some of those old Nyererean values and come out of the mixer looking more like an unbaked BRIC country. Among the many concepts that Degani deploys in his analysis is that of a dynamic equilibrium: at national scale it is perhaps easier to see that the dynamism has produced some forward motion, though its direction may not always be to everyone’s taste.

Sandwiched between an introduction that sets the scene and a conclusion that provides an update and pulls its main themes together, The City Electric comprises four main chapters, each focusing on a different locus on the infrastructural circuit of current and currency: generation, transmission, consumption, and maintenance/extension. The first chapter, “Emergency Power: A Brief History of the Tanzanian Energy Sector”, outlines the political and economic context and “upstream conditions” that led to the high costs and periodic shortages of electricity in Dar during the presidencies of Benjamin Mkapa (1995-2005) and Jakaya Kikwete (2005-15). Recurrent droughts and other failures of the hydropower network have, in Degani’s words, “prompted dubious government tenders to well-connected private companies for emergency infusions of oil-generated electricity. These public bailouts are quickly converted to private rents that in turn feed the patronage network and fund electoral campaigns.” Much of the chapter focuses on two notorious examples of this: the 1996 contract with the Malaysian-Tanzanian company Independent Power Tanzania Ltd (IPTL), and the 2006 contract with Richmond Development, “an ostensibly American company with direct ties to the prime minister at the time, Edward Lowassa.” While these arrangements severely damaged TANESCO’s operations, further privatisation of the sector and unbridled rent-seeking by the political elite were held in check by a lingering attachment to socialist values and periodic anticorruption sweeps, producing a hybrid practice and one of the dynamic equilibria that Degani describes.

Chapter 2, “The Flickering Torch: Power and Loss after Socialism”, turns the spotlight on the supply of electricity in Dar and the history of public responses to its rationing. It is based on a wide reading of documentary sources, including newspaper reports, blog posts and social media, as well as observations of the “annus horribilis” of shortages that Degani experienced himself in 2011. The resulting “ethnography of power loss” describes the narratives that circulate around the city, highlighting the explanatory voids that frustrated consumers are only too ready to fill with their own conspiratorial texts. Again, Degani skilfully weaves this account into an understanding of its political and historical context. Here he is, for example, describing what happened after 2011: “From 2012 onwards, irregular or unexplained cuts frazzled the public, giving rise to rumors and suspicions about covert and illegitimate rationing, and resonating with a wider “communication breakdown” marked by the forceful silencing of political opposition. Enduring these shifting patterns of power outages and their effects on the public nervous system, residents articulated an important and key postsocialist distinction: if it is one thing to endure absence, it is another to endure it in the absence of explanation.” While perhaps more Kafkaesque than postsocialist, the general point is well made.

In the next chapter, “Of Meters and Modals: Patrolling the Grid”, Degani and his research assistant come into their own as ethnographers of institutional practice, working in TANESCO offices and joining its patrol teams as they tramp the streets and alleyways in search of customers who haven’t paid their debts or otherwise conspired to tamper with the flows of current and currency that are the legitimate purpose of the grid. Here we learn about the compromises forged between TANESCO employees and customers in both the poorer “Swahili” neighbourhoods of Dar and their wealthier counterparts: “Faced with the evasions, protests, and obstructions of those who do not wish to be disconnected for debt or theft, some inspectors rail against customers who want it “easy” with stolen power or unpaid bills, echoing a socialist discourse of discipline and hard work. However, patrols are also well aware that the same liberalizing forces that created this indiscipline press upon them as well, in the form of diminishing pay, equipment, and job security. Some inspectors incorporate extortionist or protectionist arrangements with customers, while others maintain an ethical outlook steeped in the “socially thick” Fordist labor regime that Tanesco could still resemble even in the 1980s and 1990s”. The outcome is another of those dynamic equilibria: “Somewhere between rejecting and exploiting the putatively “Swahili” mentality of easy money, Tanesco patrol teams and customers collaboratively exercised a kind of modal reasoning about what kinds of diversions of payment are tolerable and which ones are insensible.”

In the fourth chapter, “Becoming Infrastructure: Vishoka and Self-Realization”, we find ourselves looking at all this from the perspective of the vishoka or “fixers” who work as intermediaries and mediators between TANESCO and its customers, becoming essential parts of the system and the daily struggle to maintain and extend supply. Working as unlicensed agents, they “facilitate access, expedite customer applications, provide emergency repairs, tamper with meters, or divert materials and supplies to residents in parallel markets, often by collaborating with Tanesco employees “inside” […] the institution.” As they build up the trust required to make themselves indispensable, Degani concludes that as “[b]oth parasite and channel, they are the densest expression of Tanzania’s postsocialist condition as a living circuit, a give and take of mutual adjustment and responsiveness that threatens to fall out of form; but, at least in the first decades of the twenty-first century, managed to keep spinning.” Readers will recognise the script by now, and while some might take issue with this characterisation of Tanzania’s “condition”, based as it is on selected insights into the workings of just one sector in its largest city, the challenge is to provide alternative accounts.

This summary, based largely on Degani’s own, barely does justice to the wealth of reference and conceptual sophistication that make this book such a rewarding and sometimes difficult read. With its many asides and theoretical digressions, it betrays obvious signs of its origin in the author’s doctoral dissertation (2015), though this is not directly referenced. I spotted several typos and other mistakes in the text, especially in Swahili words and phrases that will have been missed by English proofing tools (note also the mistranslation of vibatari as “matches” rather than small oil lamps). These, however, are mere quibbles. My personal recommendation would have been to streamline the argument of the thesis and provide richer ethnographic documentation, with less reliance on the relatively few anecdotes that bear its theoretical load, providing instead more case material on relationships and interactions in particular places, for example in sample neighbourhoods and the roadsides where “fixers” and others congregate. But urban anthropology and the ethnography of complex institutions are easier said than done, and Mike Degani deserves praise for his own ingenuity and the way in which he has negotiated this difficult terrain and produced such an illuminating study. General readers as well as fellow academics and anthropologists will find much in his first book to stimulate reflection and debate and, like me, will no doubt look forward to reading more.

Martin Walsh Martin Walsh is the Book Reviews Editor of Tanzanian Affairs.

ZAMANI: A HAUNTED MEMOIR OF TANZANIA. Jane Bryce. Cinnamon Press, Birmingham, 2023. 226 pp. ISBN: 9781788649865 (paperback). £13.99.

Zamani starts with a quick introduction to Jane Bryce’s childhood involvement in Tanzania as she flies over Kilimanjaro into the country for the first time since she left in 1968 at the age of 17. She briefly sketches the lives of her parents, their meeting and their subsequent marriage, and then she continues by describing how her father joined the Colonial Office and was posted to the Forest Department in Tanganyika, to the Rondo Plateau in the Southern Province (present Lindi Region), with a view to introducing sound forest management. His first job was to map the 32,000 acres of the forest, on foot. Jane’s mother was not one to sit at home waiting for her husband to return, but accompanied him on these journeys through the forest, perhaps covering 80 miles in six days, carrying on with this until late in her pregnancy with Jane. Referring to her mother’s diaries, she describes the life at this time, the isolation, the hardships, the lack of food, the wild animals.

Jane then jumps to the present and gives an account of her travels to Lindi, to explore the place of her birth, which she hadn’t visited since she left at the age of three. She meets people who knew her father, all old men by now, but delighted to encounter her and to spend time telling tales of the past. This becomes a theme which threads through the book since there are many more old colleagues in Moshi – meeting old-school government forest officers, now in their 70s, who remember her father. There are photographs of kindly faces, seamed with experience, throughout the text. One cries out, “The daughter of Bwana Bryce!” and she immediately feels part of the story of Tanzania, not merely an outsider wandering the country like a tourist. This fits in with another of her themes, that of identity and belonging.

At the end of their time on Rondo, the family moved first to Morogoro and then north to Moshi. Their time in Moshi is the central part of the book, since this is the place Jane remembers as a child, and where she grew up. She compares the Moshi of today with the one she remembers and is pleased to find much is similar – “I could walk with confidence in any direction and know without asking where I was going”, she tells us. She recounts her daily life as a child, her friends, the social gatherings with other colonials, their holidays on the coast via the old steam trains, the primary school she went to. Once she turned 13, she then left her comfortable home and made the long and difficult journey to the boarding school in Lushoto, filled with the usual horrors of boarding schools – matrons, food, inflexible rules – during that period. After that, she was sent to England, to study at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, a foreign country in many ways for her, which she hated as much as the Lushoto school. In 1968 her father is suddenly told he must leave Tanzania. The sisters are informed by letter, their mother telling them, “We have been so lucky with our happy life in dear old Moshi all these years it has been home to us. Sorry to have to send you news which will distress you so much.” It throws Jane’s life out of kilter, and it takes another 36 years for her to return to Tanzania.

The title, Zamani, meaning ‘long ago’, is contrasted with sasa, meaning ‘now’, and Jane explores how on her return, the two seem to co-exist for her, as she sees the present as a sort of overlay of the past. She weaves her narrative almost seamlessly, jumping from the past to the present, with brief digressions into history, politics, mythology. The history snippets are not long enough to slow down the narrative but are painted in as a necessary and helpful backdrop to what she is discussing, and this was one of the aspects of the book which I liked the most. She explains the history of the area she lived in, looks into the origins of the peoples who originally lived here and their languages and local leaders, describes the forest policies and their effects, the colonial times and then the transition to independence in the 1960s, as well as the country under the Germans before the British took over.

I was concerned through the first chapters of the book that Jane would sustain the colonial attitudes inherited from her parents, imbued as a child, but she uses her later trips to Tanzania to question her assumptions at the time, the rigid, rulebound ways of her parents’ generation. She discusses the house staff in their Moshi home, whom she accepted were always there, always ready to help, and realises she knows little about them, even their surnames, apart from their daily lives with the family. The colonial set-up comes in for critiques too, and the fact that they never knew any African people, apart from their house staff, and perhaps once a year took tea with a well-to-do Indian family but never invited them back. However, her father clearly got on with his African colleagues, and in meeting some of them almost 40 years later, Jane experiences a different view of the country she loved so much.

Kate Forrester

Kate lived in Tanzania for 15 years, working as a freelance consultant chiefly in social development, and carrying out research assignments throughout the country. She now lives in Dorchester, where she is active in community and environmental work.

MUSLIM CULTURES OF THE INDIAN OCEAN: DIVERSITY AND PLURALISM, PAST AND PRESENT. Stéphane Pradines and Farouk Topan (eds.). Edinburgh University Press in association with The Aga Khan University, Edinburgh, 2023. 356 pp. ISBN: 9781474486514. (ebook free to download from https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/62324; also available for purchase as a hardback).

There has been a boom in Indian Ocean studies in recent years, with a plethora of edited collections now on the market. This book is the latest addition to a series on “Exploring Muslim Contexts” overseen by the distinguished scholar of Swahili literature and culture Farouk Topan, who has edited this volume in collaboration with the archaeologist Stéphane Pradines. As their blurb declares, it “examines the role of Muslim communities in the emergence of connections and mobilities across the Indian Ocean World from a longue durée perspective. Spanning the 7th century through the medieval period until the present day, this book aims to move beyond the usual focus on geographical sub-regions to highlight different aspects of interconnectivity in relation to Islam. Analysing textual and material evidence, contributors examine identities and diasporas, manuscripts and literature, as well as vernacular and religious architecture. It aims to explore networks and circulations of peoples, ideas and ideologies, as well as art, culture, religion and heritage. It focuses on global interactions as well as local agencies in context.”

Students of the history and practice of Islam around the Indian Ocean will find much of interest here, beginning with the editors’ handy introduction to the historiography of the region and its Muslim cultures and heritage. The main text is split into two parts, “Muslim Identities, Literature and Diasporas” and “Monuments and Heritage in Muslim Contexts”, with eight chapters under the first heading and seven under the second. Three consecutive chapters in Part I are of direct relevance to the history of Zanzibar and its wider sphere of influence: Beatrice Nicolini’s analysis of Omani rule (“Muslim Identities of the Indian Ocean: The Ibadi Al Bu Sa’id of Oman during the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries”), Valerie Hoffman’s deep dive into social and cultural relationships as revealed in contemporary manuscripts (“Religion, Ethnicity and Identity in the Zanzibar Sultanate”), and Farouk Toupan’s study of the changing roles of Swahili women (“Transcending Boundaries: Sayyida Salme/ Emily Ruete and Siti binti Saad”), which homes in on the lives of two of the archipelago’s most famous daughters, both of whom challenged the status quo, albeit in very different ways.

Part II opens with Eric Falt’s discussion of “The Indian Ocean as a Maritime Cultural Landscape and Heritage Route”, which makes a case for its study and promotion in just such terms. This short presentation is followed by two longer chapters about the history and archaeology of the Swahili coast and islands: Stephen Battle and Pierre Blanchard’s introduction to heritage and conservation (“Indian Ocean Heritage and Sustainable Conservation, from Zanzibar to Kilwa”), and Stéphane Pradines’ illustrated account of the role of trade in the spread of Islam and associated mosque architecture (“Early Swahili Mosques: The Role of Ibadi and Ismaili Communities, Ninth to Twelfth Centuries”). As he has done elsewhere, Pradines highlights the part played in the early development of Islam by what are now considered to be religious minorities within the faith, before the widespread adoption of Sunni Islam in Africa and this region. He concludes by referring to “the permeability between Sufism and Shi.a spirituality”, and it would be interesting to know more about this and how it is reflected in modern language and practice.

Readers will find topics worth exploring in other chapters too. Fortunately, this informative and well-produced volume, which is the first publication of the Indian Ocean programme in the Aga Khan University’s Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations, has been made open access and can be downloaded for free by those of us who can’t spare £85 for the hardback.

Martin Walsh