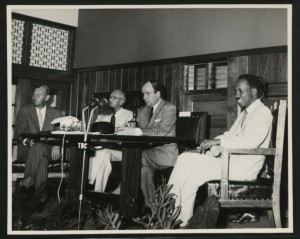

President Nyerere meeting with VSO volunteers in 1977 - see article on VSO in Tanzania later in this issue

President Nyerere gave hundreds of interviews before, during and after his terms of office. We are grateful to Peg Snyder/Paul Bjerk/Juhani Lomppololle/ Aili Tripp for digging out and transcribing an interview given by Mwalimu in 1971 to a Finnish journalist. Extracts:

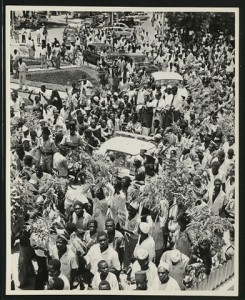

Nyerere: … In 1961, what was our major ambition? Our major ambition was obviously to survive as a nation. We have survived as a nation, we have consolidated ourselves as a nation, and we have consolidated our independence. I suppose really, quite frankly, this is our biggest achievement. Only as an independent country could we do such things as raising standards of living, increasing education, and so forth. Well I can’t say we have achieved all we would have liked to achieve.

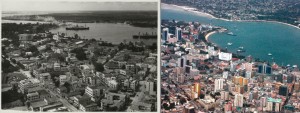

Questioner: You place a very heavy emphasis on rural development… but in this report, you say, “indeed more money has in fact been spent on urban developments, industrial and business development, than on rural areas, in this post-Arusha period”. So what could, in your opinion be the reason for that?

N: One is habit. The other is the ease. It’s easier to invest in urban areas than to invest in rural areas. Simply habit. Habitually this is what happens, you establish a habit where investment flows into the urban areas because it flows there habitually. And apart from habit you have certain facilities which have been put in urban areas, and if you are going to use these facilities properly, really you are forced to put something in … And I say secondly, it’s easier to plan a textile factory than to plan a village. A village of three thousand workers, three thousand peasants requires a great deal more, more innovation if you like. We are less used to this. Basically I think, habit. We have to break the habit of thinking in terms of employment. Because even if, now, if we want to build a school, if we want to build a secondary school, …the majority of the students who go into this secondary school are from the peasant areas, peasant sons and daughters. But we will have by habit put the school in an urban area…

Q: What are your reservations about foreign development corporations?

N: I think reservations would be quite normal. Quite normal. It is always a matter of judgment what country we are dealing with. Very often rich countries use their ability to assist poorer countries in order to dominate these poorer countries, to build spheres of influence, to keep other competitors, other nations out. And they regard them as competitors. A kind of jealousy develops. I want to build a railway, and I try to get some money from the Western world; if I don’t get that money then I try to get it from China. The fellows do not want to give the money, and then they ask why? why? This is introducing the Chinese to Tanzania. There is kind of feeling… keep the Chinese out, Tanzania is our sphere of influence. You know the Chinese should be kept out. It becomes a kind of instrument. Aid becomes an instrument of imperialism. And this is really the first reservation. Secondly, aid should help us to do what we want to do. It’s no use some country coming here with some brilliant idea that they want to do xyz. And in our own priorities we don’t want to do xyz, it is something that can wait until the 2000s.

Q: Do you see anything remarkable in the Chinese assistance causing any changes in the non-alignment policy?

N: I don’t see why it should. Non-alignment has never meant that a non-aligned country should have nothing to do with an aligned country. This has never been a definition of non-alignment. It has the meaning that we must never behave in our relations with aligned powers as if we belonged to their blocs. We don’t. And we have relations with China just as we have relations with the Soviet Union or relations with the United States. We see no reason why it should affect our nonalignment. Actually we feel it is an expression of our non-alignment. We would find it ridiculous that it is not alright for us as a non-aligned country to ask the Soviet Union or the United States to build a railway for us. But somehow it becomes wrong for our non-alignment if we ask China to build a railway for us (laughter).

Q: Your views of the present dispute between Tanzania and Uganda amidst reports of border clashes. Do you think there will be a danger of war?

N: Well, what you really want one never knows. I mean it takes two, to bring about war. But actually it doesn’t take two, it can take only one. So in that sense, if one side decides to be foolish, this foolishness can lead to a dangerous situation. But frankly, I don’t believe that these troubles on the border can cause, can be developed into anything more than troubles on the border.

Q: What is your comment on the British Foreign Secretary Sir Douglas Home going to Salisbury trying to negotiate a settlement to the Rhodesia problem.

N: Our views have been very clear for years and they’ve not changed. It was Sir Alec, when he was Prime Minister of Britain, who formulated the so-called five principles. And it was while he was Prime Minister that we said we don’t accept these principles as a basis of granting independence to Rhodesia, because they mean granting independence to a country on the basis of minority rule. And we don’t accept this. And it is really this which he’s going to negotiate with the Rhodesians. He’s going to negotiate with the White Minority there. To hand over to them the government, the same thing that they did in South Africa. They want to create a second South Africa. This is really the whole basis of these talks, to create a second South Africa, and we’ve always said we can’t accept this. What are we expected to say? ‘This is fine’?

Q: Is there any settlement which you would not consider to be a sellout?

N: Any settlement. Any settlement on that basis would be a sell-out. Handing over five million people to the good will of a tiny minority, and believing that this minority at some future date will hand over power to the majority. It doesn’t happen.

Q: You said in September this year in this report, Tanzania has paid a heavy price in economic aid for her stand on these matters. But neither in relation to Britain nor any other country have we wavered on the policies we believe to be right because of our desire to develop our country at maximum speed. Have you ever doubted?

N: Have I ever doubted our policy? Never.

Q: But you have paid a price?

N: Well surely you must pay a price for your freedom, if it is really freedom. If we wanted to remain a colony we could have remained a colony. As a colony our responsibilities wouldn’t hold. I got my grey hair in our second year of independence. My hair was black, completely black when we became independent, and in two years it had gone grey, because of some of the problems of independence. If you don’t want the problems of independence don’t become independent.

Q: Do you think that the freedom fighters will succeed?

N: Why not? If we didn’t believe they will succeed then there is no point in fighting is there? There’s no point in the struggle is there? Unless it is a kind of religion. There’s no point in struggling for freedom unless you believe you are going to win. And if we believed these people are wasting their time, why should we be working to get support for them throughout the world. We are trying to get the world to understand this problem in southern Africa, and to understand that these people are struggling for human rights, and they must be helped until they win. If we didn’t believe they have a chance of winning there is no use helping them, or trying to get their world to help them.

Q: Now this is the last final question. Mr. Karalov has suggested that you have been translating William Shakespeare into Swahili. Have you yourself been writing any poems?

N: No. Not poems in that sense, not poems in that sense of William Shakespeare. Everybody. Every literate person has written some verse. So that’s all. This question of Shakespeare is really you have read Shakespeare, so have I. Some. I have not read Shakespeare, I have read one or two books, not more than one or two books. And then sometimes I, because of my interest, not so much because of my interest in Shakespeare, but in Swahili. I have translated some bits of Shakespeare into Swahili because of my effort to learn Swahili rather than to translate Shakespeare.