by Martin Walsh

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AID AND ACCOUNTABILITY: THE RISE AND FALL OF BUDGET SUPPORT IN TANZANIA. Helen Tilley. Ashgate, Farnham, Surrey, 2014. x + 157 pp. (hardback). ISBN 978-1-40946442-6. £95.00.

This short book adopts an institutionalist or functionalist approach to foreign aid, in which governments are controlled by corrupt elites, donors make resources available to support their domestic agendas or to achieve foreign policy objectives, and procedures and practices have grown up to facilitate this while largely concealing what is going on from the public in both donor and recipient countries. The formal processes of accountability, including monitoring missions and end-of-project reports have little impact when the recipients have different objectives from the donors. This theory is supported by two chapters on the politics of foreign aid in Tanzania, mainly in the Mkapa and early Kikwete years, drawing on the author’s experiences as an ODI Fellow in the Ministry of Finance and as a consultant working for various donors.

The author follows Mustaq Khan who shows that corruption can sometimes be functional, but gives little attention to its downsides – cynicism and a loss of faith in the capabilities of the state and of politics generally. There are indeed possible benefits, in the short term, if corruption leads to economic activity which otherwise would not take place. But if resources are syphoned off and little or no investment in productive activity takes place, there are no benefits from corruption, only disbenefits, and a general loss of morale in which the whole political class becomes discredited. The author is much too generous to the aid professionals (both academics and consultants in the private sector) who have connived in this and made it possible for government-to-government transactions to continue when they were aware that they were achieving little that could be described as development.

The analysis is strangely static. It does not deal well with the pressures that build up on a political party that has ruled for 50 years, the creation of structures and movements outside the formal political processes, or the abilities of populations to grow and survive, and sometimes prosper, without much useful support from the state. It made me long for more specific case study material, for example the stories of a small number of aided projects or programmes told from both sides of the divide (together with the perspective of the supposed recipients) showing how weasel words and low-key reports and presentations were used to cover up or play down failures, or the distribution of the spoils from what was presented as good works, and how this was justified. Studies of that sort would have been fun to read, if still depressing, and at least have offered some hope and challenge for whoever gets involved in these activities in the future.

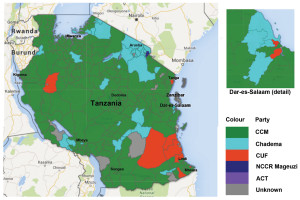

Democracy is presented as a process in which political parties survive by making promises to voters which they will deliver if elected. Since most taxes are indirect – import and excise duties – voters are not made aware of the consequences of more government spending rather than less. So accountability passes to external agencies – donors and bankers. But their leverage is less when interest rates are low, banks and donors are looking for opportunities to place their money, and where a new tranche of donors from the East are less demanding. But the experience of elections in Tanzania shows that it is also a judgement on the past, especially if promises made last time have not been delivered, and even the most entrenched elite cannot take victory for granted.

The case study does not present statistics showing the quantities of budget support (or its cousin, basket funding) negotiated in Tanzania, and focuses on the relative power of the two parties in a bargaining situation. But a note in passing demonstrates the limitations of this kind of functionalism. The author notes that “allowances and workshops, with the associated benefits of per diems, meals and transport funding” were in 2009/10 estimated to cost “the equivalent of one third of the government wage bill and 11 per cent of the government’s total recurrent spending” (p. 112), and then comments that the Government was unable to control this. No doubt that was how it appeared at the time. But cutting this kind of posho was one of the first acts of President Magufuli – showing that at least one leading figure could see the contradiction and was willing to take the political risk of trying to do something about it. Aid that does little more than prop up dysfunctional and often oppressive regimes is a fraud on the publics in both donor and recipient regimes, and academic writers should take care not to give the impression that this is inevitable or acceptable to any of them.

Andrew Coulson

LOOKING BACK, LOOKING AHEAD – LAND, AGRICULTURE AND SOCIETY IN EAST AFRICA. A FESTSCHRIFT FOR KJELL HAVNEVIK. Michael Ståhl (editor). Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, Uppsala, 2015. 240 pp. (paperback). ISBN 978-91-7106-774-6. £13.90. Also available for download at http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:nai:diva-1935

Rural communities in East African countries face many challenges: high population growth, increasing land scarcity, intensification of land conflicts, climate change, persistent food insecurity, rural-urban migration, and largely stagnant agricultural productivity levels. After decades of neglect, the question of agricultural transformation in Africa is back on the policy agenda, and there is a heated debate on whether this should be based on developing the productive capacities of smallholder farmers or on enrolling foreign direct investments to nurture large-scale farming. This holds true for Tanzania, which has been one of the prime frontiers of what has been labelled the “global land grab”. At the same time, it is an exemplary case for the rise of a commercially oriented agricultural policy agenda in Africa, which manifests itself in pro-large-scale farming initiatives such as Kilimo Kwanza, SAGCOT and Big Results Now.

Against this backdrop, it is welcome that several of the contributions to this book, published as a Festschrift for renowned agrarian scholar Kjell Havnevik, focus on the issue of agrarian change in Tanzania. Most outstanding here are the historically rich contributions of Deborah Bryceson (‘Reflections on the unravelling of the Tanzanian peasantry, 1975-2015’) and Andrew Coulson (‘Small-scale and large-scale agricultures: Tanzanian experiences’), on which the remainder of this review will focus. Both deal with the changing positionality of smallholder farmers (or “peasants”) within the politico-economic and agricultural policy landscapes of Tanzania. Both agree that promotion of large-scale farming favoured by sections of the Tanzanian political and business elite may lead to new enclosures of land and the dispossession of rural populations. However, they differ on how they imagine the future of the “peasantry”. Bryceson provides us with a rather pessimistic agrarian history of Tanzania, which starts with the “Tanzanian nation-state […] originally founded on and designed with peasant’s political, economic and social aspirations in mind” (p. 10) and ends with the “disintegration” (p. 24) and “self-liquidation” (p. 26) of the ‘peasantry’. After three decades of neoliberalisation that did away with Nyerere’s egalitarian vision of development, as well as in the wake of the neomodernist promotion of large-scale farming, Tanzanian peasants seem to be bound to become a “distant memory” (p. 26). The recent discovery of natural gas and the shifting policy priorities potentially associated with it will only accelerate this decline. This pessimism is familiar from Bryceson’s earlier work on the same subjects.

Coulson is equally critical, but much more optimistic about the potential effectiveness of a smallholder-oriented development strategy. The strength of Coulson’s contribution is twofold. First, unlike Bryceson, he engages critically with the term “peasant”, dismissing it as an empty signifier that is anachronistic and imbued with developmentalism. Second, he tests the theory that “small farms can, in appropriate circumstances, compete with or outperform large [farms]” (p. 65). Given past experience, he cautions us about the current craze for large-scale farming schemes: “Tanzanian planners have exaggerated the potential of large farms and the easy availability of land, and underestimated the challenges they face. In particular, they have exaggerated the potential for irrigation” (p. 67). Coulson argues that farm productivity levels could be increased significantly by ensuring that farmers have access to sound marketing arrangements that provide them with fair prices, credit, inputs and agricultural expertise. Cases such as Vietnam or China, which heavily relied on a smallholder-oriented development strategy, could serve as models.

Both authors make valid points, but Coulson’s nuanced account is much more useful for constructive thinking about the current agricultural impasse in Tanzania and other African countries. However, two crucial issues seem to be largely absent from every Tanzania-focused contribution to the book. First, I miss an account that addresses the question that Prosper Matondi raises in her excellent chapter on ‘Land reform, natural resource governance and food security’: “What type(s) of governance institutions and mechanisms will lead to improved livelihood outcomes and environmental sustainability in rural Africa?” (p. 209). Second, we still need a more thorough engagement with the question of how the shift towards large-scale farming in Tanzania is related to changes in national class relations and how in turn these relations shape the dynamics of agricultural policy-making, implementation, and investment. The frictional implementation of Kilimo Kwanza and SAGCOT suggests that such relations are much more multifarious than a crude political economy analysis suggests.

Altogether, this book is a mixed bag. The contributions differ in scope and depth, and many do not match the quality of Bryceson’s and Coulson’s chapters. Several of them also lack a clear theoretical framework.

Stefan Ouma

THE GROUNDNUT LINE: THE STORY OF THE SOUTHERN PROVINCE RAILWAY OF TANGANYIKA. David Burton. Published by the author, Telford, 2014. 48 pp. (paperback). £8.99. Available directly from the author at 53 New Church, Wellington, Telford, Shropshire, TF1 1JX (UK cheque or postal order), or via eBay (item no. 131689627186).

The Groundnut Scheme planned for Tanganyika in the late 1940s has gone down in history as one of the worst financial decisions made by the British government in its overseas colonies. Following the end of the Second World War there were severe shortages of consumable oils and fats, and a proposal to clear and farm large areas of bush to produce groundnuts in Tanganyika was pushed forward with little idea of the difficulties involved. Poor planning, unsuitable equipment and incompetent personnel compounded the poor choice of location and lack of rainfall. The major site chosen for the planting was Nachingwea, 90 miles inland and with no communication either by rail or road. A railway was planned with the initial starting point at Mkwaya at the top end of Lindi town creek, but this proved unsuitable for the planned port, which was later built at Mtwara, 40 miles away. Tanganyika Railways were tasked with the construction of a metre gauge railway which was begun in 1947.

The massive expenditure of £35 million on the Scheme with little return caused the government to abandon it on 9 January 1951. Despite this, Mtwara port was built and the new rail link between there and Nachingwea completed in 1954. This used steam and diesel locomotives and became known as the Southern Province Railway (SPR). The two major types of steam locomotives were the NZ Indian 4-8-0 Class built in 1915, and the 22 (G) 4-8-0 Class dating from a year later. The diesel locomotives were shunters seen in other parts of the East African system, namely the 80, 81 and 83 Class as well as three Wickham passenger railcars. The latter had been ordered by the Kenya and Uganda Railways before the war but the Swiss Saurer engines did not arrive until after its end. After use on a line in Kenya they were transferred to the SPR. The envisaged tonnages of groundnut and other freight on the line never materialised and despite the backing of the East African Railways organisation and an additional extension to Masasi the line was closed on 1 July 1962 with a huge loss.

The Groundnut Line by David Burton is an excellent addition to the East African railway enthusiast’s library and tells the story of the earlier Lindi tramway built by the Germans before the First World War and the background to the SPR and its expansion until its closure in 1962. It includes numerous illustrations and maps and three specially commissioned works by the railway artist David Charlesworth, including a delightful colour cover depicting an NZ 4-8-0 steam locomotive running along the shoreline near the town of Mikindani. The book is divided into two sections, the history of the scheme and the railway up to its closure and subsequent dismantling, and an appendix of diagrams and photographs of the steam and diesel locomotive motive power. A detailed glossary of names, bibliography, additional reading and index complement a well-produced and interesting history of one of the lesser known railways in East Africa.

Kevin Patience