by Ben Taylor

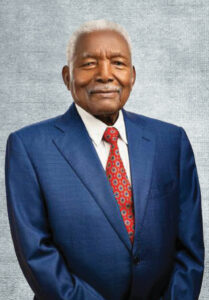

Ali Hassan Mwinyi

Tanzania’s second President,

Ali Hassan Mwinyi, died on February 29, 2024 at the age of 98 after battling lung cancer. Popularly known as “Mzee Rukhsa” (Mr Permission), Mwinyi served as President of the United Republic of Tanzania from 1985 to 1995. A teacher by profession, he also briefly held the offices of President of Zanzibar and Vice President of the United Republic.

President Mwinyi earned his nickname primarily for the economic reforms he brought in, by which restrictions were lifted on many things which had previously been prohibited or tightly controlled – import restrictions, private enterprise, television ownership by individuals and more. Over time, relaxations extended to political freedoms, including independent media and multi-party democracy.

He took office at a time when the country’s economy was struggling, and many – including the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – were urging liberalisation. But having been hand-picked by his predecessor, Mwl. Julius Nyerere, who remained as chair of CCM, the widespread expectation was that this shy new leader would be little more than a puppet. People should “not expect many changes,” wrote The Economist, as “Mr Mwinyi is Mr Nyerere’s man.”

Mwinyi skilfully negotiated a balance between loyalty to Nyerere and driving reforms. He described himself as an anthill succeeding Mount Kilimanjaro. Given the respect with which Nyerere was still held, there can be little doubt that Mwinyi must have had some form of approval from his predecessor for the measures that he introduced – indeed, in stepping aside, Nyerere had admitted that Ujamaa had failed and said he had decided it was time the country tried another leader. But the transformation was dramatic. Mwinyi essentially dismantled Ujamaa and the Arusha Declaration, though he insisted he was not usurping these but rather perfecting them to keep up with changing times.

During his first address as President to Parliament in 1986, Mwinyi promised to resume negotiations with the IMF and World Bank, arguing that any resulting agreement would be beneficial to citizens. Later that same year he made an agreement with the IMF to receive a $78 million standby loan – Tanzania’s first foreign loan in over six years. Bilateral donors approved this austerity plan and agreed to reschedule Tanzania’s debt payments for a period of five years, requiring that Tanzania pay only 2.5% of their debts in the meantime. With the economy on the brink of collapse, the reforms were seen as having as saved the economy. Severe food, fuel and foreign currency shortages were alleviated, and economic growth picked up.

Political reforms followed a few years later, including the re-introduction of multi-partyism. “We’re not an island,” and so can’t be unconcerned with global affairs,” he said in explanation. These reforms were left incomplete, however, with Mwinyi and the CCM leadership deciding against enacting many of the changes proposed by the Nyalali Commission.

Mwinyi’s leadership was not without criticism. In particular, his decision to allow political leaders to run private businesses was criticised for opening up the way for high corruption levels during and beyond his time in office. It was said that his decision to open the windows and allow the fresh air to come in, but that this also allowed insects inside as well.

President Mwinyi left office peacefully in 1995 at the age of 70, after serving two five-year terms of office. In retirement, he kept a relatively low profile, but released his memoir, Mzee Rukhsa: The Journey of My Life, in 2021, and also served as President of the Britain-Tanzania Society.

Speaking at the burial ceremony, President Samia Suluhu Hassan paid tribute. “Mr. Mwinyi was a wonderful leader who highlighted

the importance of translating leadership into service to people and maintaining diligent and ethical services,” she said.

“Throughout my tenure, I’ve tried to follow his steps, though I am uncertain of my success. I’m not sure if I fitted his shoes. But all I can tell is that the library has burned down,” she lamented.

King Charles released a statement that read: “It was with great sadness that I learned of the death of former President Mwinyi. He was a true friend of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth, and a leading figure in Tanzania’s economic and political development.”

He is survived by his two wives and a number of children, including Zanzibar’s current President Hussein Mwinyi.

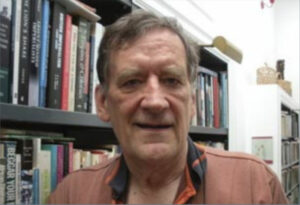

Edward Ngoyai Lowassa

Former Prime Minister of Tanzania,

Edward Ngoyai Lowassa died on February 10, 2024 at the age of 70. He served as Prime Minister from 2005 as a close ally of President Jakaya Kikwete. However, his time in office was shortened by a corruption scandal that led to his resignation in 2008, and he never achieved his ambition of becoming President.

Lowassa first sought the nomination of Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) as its presidential candidate in 1995 but was eliminated in the early stages by an intervention from former President Julius Nyerere, who argued that Lowassa was not then correct material for the Presidency – a marked non-endorsement that followed him for years.

Following the 2000 general elections, Lowassa was appointed Minister of Water and Livestock Development and made his name as a hardworking minister. He stood firm against a colonial-era treaty in order to supply water from Lake Victoria to the towns of Kahama and Shinyanga, and took similarly decisive action when the privatised water utility in Dar es Salaam was seen as failing.

As Prime Minister from 2005, Lowassa again demonstrated his ability to get things done, delivering a massive expansion in secondary school provision across the country.

However, it was not long before he became embroiled in the “Richmond” emergency power generation scandal. In 2006 as the nation faced serious power shortages due to low water levels in hydropower facilities, the government invited investors to apply for the production and supply of over 100 megawatts. A US-based firm, Richmond LLC won the tender, but it soon emerged that the process had been marred by irregularities. A parliamentary committee concluded that Richmond was a briefcase company and found the contract to have been fraudulently entered into. Further, while Richmond was contracted to provide 100MW each day, their generators arrived late and did not work as expected, and yet the government was reportedly paying the company more than $100,000 a day. Lowassa’s office was then accused of extending the contract against official advice. Lowassa denied culpability, but eventually, in February 2008, he resigned as Prime Minister along with two other cabinet ministers.

Lowassa continued to court – and win – the support of the CCM hierarchy as well as the wider public, and he made no secret of his continued presidential aspirations. In 2015, as a frontrunner, his name was struck from the list of potential CCM nominees following an intervention by party elders, to the shock of many.

Shortly afterwards, he defected from CCM to the main opposition party, Chadema, where he ran a presidential campaign against the CCM nominee, John Magufuli. He was unsuccessful but achieved 39.9% of the vote, the highest number by any non-CCM candidate in the country’s history. Three and a half years later he rejoined CCM.

Lowassa was a divisive figure in Tanzania politics. His supporters pointed to his unrivalled ability to get things done, while his critics pointed to his massive personal wealth and portrayed him as the embodiment of political corruption.

Speaking at his funeral, President Samia described Lowassa as “a force to be reckoned with.” She described him as creative and said he had sacrificed a lot for national development.

Freeman Mbowe of Chadema, said Lowassa’s 2015 campaign had given CCM a challenge on a level they had never seen before.