by Ben Taylor

Six months into the presidency of President Samia Suluhu Hassan, it remains unclear what her leadership will bring. In some areas she has shown a clear change of direction compared to her predecessor, while in others the difference brought about by the change of leader has been barely discernible.

There are three areas where the change is considerable. The first of these is her handling of the Coronavirus pandemic, where she has abandoned some of the more idiosyncratic approaches employed by President Magufuli [see separate article].

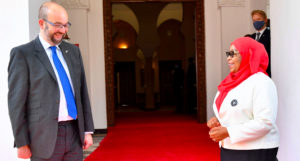

Second is her diplomatic outlook. Her predecessor rarely travelled outside the country and delivered a pugnacious style of foreign policy, based on the starting assumption that everyone else’s intentions towards Tanzania are malign. In contrast, President Hassan has employed a more open style and a gentler touch. And she has travelled more: already visiting Uganda (twice), Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda, Malawi, Mozambique and Zambia, meaning she has made as many foreign trips in her first six months as President Magufuli took in his entire time in office.

She has taken steps to patch up relations with Kenya, particularly over trade in agricultural produce. A Presidential visit to Kenya delivered a bilateral deal to abolish the restrictions that Nairobi had imposed on Tanzanian maize, which in turn led to a reported six-fold increase in maize exports to Kenya.

Under her leadership, the Tanzanian government has also ratified the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement. This is expected to attract more investors and provide access to a large market for the country’s produce and workers. If implemented successfully, the newly formed free trade area will unlock a regional market of 1.2 billion people with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) of $3.4 trillion for international investors. The AfCFTA agreement, signed in March 2018, hopes to double intra-African trade. The official start of trading was delayed in 2020 by the Coronavirus pandemic, but it began officially on January 1st 2021. Tanzania now joins 41 other countries as part of the agreement.

The third area of difference is her attitude towards economics, and business in particular. President Magufuli’s “bulldozer” style encompassed his approach to economic matters, including a no-nonsense stance on taxation and an aggressive posture towards the business interests of those he perceived as working against him. Foreign investors complained that the business environment had become more difficult. The economic effects of these positions are hard to assess with confidence, particularly given how politicised official economic data became under his Presidency – to the point where the IMF and World Bank pointedly stopped trusting official figures. Nevertheless, the effects are widely perceived to have included both a tightening of economic conditions and an increase in tax revenues.

President Hassan, in contrast, has made overtures to investors and business leaders. She has said that henceforth, tax collection would focus on compliance instead of coercion and intimidation. She has also promised that her government will actively listen to business leaders, so it can understand and address their complaints.

At the same time, the new President has attracted criticism for the way her government has turned its tax-raising attention to ordinary citizens – through the mobile money tax [see Economics and Business section in this issue], and through other measures that hit the poor hardest, such as refocussing building taxes on renters rather than landlords.

On domestic political matters, the extent to which President Hassan has diverged from President Magufuli’s heavy-handed style remains highly uncertain. Despite initial signs of a relaxation of restrictions on political activity and freedom of expression, more recently there have been growing concerns among pro-democracy groups that the new President’s approach may have more in common with her predecessor’s than previously thought.

Most obviously, the arrest and detention of opposition leader Freeman Mbowe on terrorism charges [see separate article] provoked such concerns. The extent to which the President was involved in the decision to charge Mbowe is unclear, but it is unlikely that it would have gone ahead without her approval. She has also spoken about the case, telling the BBC that the charges were not politically motivated and arguing that the country remains very democratic. She added that while the case is in court she is not at liberty to discuss it in detail, and advised that the judiciary should be left to do their job.

Similar concerns have been prompted by the suspension of two newspapers. In early September, Raia Mwema, a leading Swahili-language weekly, was suspended for 30 days, for “repeatedly publishing false information and deliberate incitement,” according to Gerson Msigwa, the government’s chief spokesperson. He cited three recent stories, including one about a gunman who killed four people in a rampage through a diplomatic quarter of Dar es Salaam. The article linked the gunman to ruling party Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM), according to Msigwa, adding that the article violated the 2016 Media Services Act.

The other suspension, introduced several weeks earlier, arguably hints at perhaps the greatest challenge President Hassan faces. In this case, the CCM-owned Uhuru newspaper was suspended for 14 days, after publishing a front page story under the headline: “I Don’t Have Intentions to Contest for Presidency in 2025 – Samia.”

A power struggle underway?

To suspend her own party’s newspaper, particularly given the subject of the offending article, suggests an internal struggle for control within CCM. President Magufuli had built up a party machinery filled with his supporters. Many of these are uncomfortable with some of the changes President Hassan has brought in. Others are more pragmatic, adjusting their stances to align with the new circumstances. Yet more are looking anxiously (or ambitiously) towards 2025, when the next Presidential elections are due.

The constitution is clear: President Hassan is entitled to run again for President in 2025. President Magufuli would not have been eligible to do so. (Unless he had brought in constitutional change to term limits, which had looked possible but which is now a moot point.) Thus any party figure with presidential aspirations faces the probable reality that those ambitions will have to be delayed by five more years. There are no doubt some prominent and influential figures and their supporters who are frustrated by this, some of whom may have wished to foster an expectation President Hassan should merely serve out President Magufuli’s second term and then step down in 2025.

Internal power struggles within CCM are nothing new. President Magufuli himself became leader of the party without a strong base of support – essentially a compromise candidate – and it took some time (and a strong will) before he was able to stifle the grumblings of internal dissent and shape the party in his own image. The popularity he gained with the public for his no-nonsense approach and vocal patriotism made it hard for opponents within the party to stand up to him, and he came down hard on anyone who expressed critical views.

Nevertheless, President Hassan faces an even more difficult challenge. Having become President on the basis of being Vice President at the time of her predecessor’s untimely death, and having essentially been hand-picked for Vice President by a tiny group of party insiders rather than by the membership at large, she starts with an even weaker power base than President Magufuli had. She is yet to prove herself with the public. And she has to contend with two large sets of party members who are pre-disposed to remain lukewarm towards her: die-hard Magufuli supporters and those with presidential ambitions of their own.

These challenges may also be showing up in President Hassan’s handling of other matters – such as Covid-19, or even the arrest of Mbowe. Would she be inclined to do things differently if she didn’t have internal party management matters to consider? Is she picking her battles carefully, choosing where to apply her limited political capital and where to let things go?

Even beyond politics, Covid, diplomacy and economics, there are other matters of significance where the President is yet to make her direction clear. Will she maintain President Magufuli’s hard-line approach to corruption and waste in government, or might we see the return of these problems that plagued the country in earlier periods? How will she handle the legacy of the mega-projects – the Stiegler’s Gorge dam, the purchase of aircraft for Air Tanzania – that may prove more complicated to manage than to introduce?

No-one is yet in a position to conclude with confidence what President Hassan’s style or focus will be. To date, this could perhaps be summarised as a gentler and more open version of Magufuli-ism. But isn’t a compassionate bulldozer a contradiction in terms?