NYERERE – THREE BOOKS

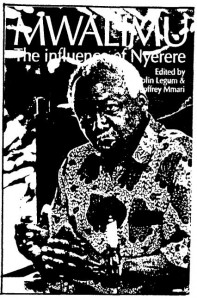

MWALIMU – THE INFLUENCE OF NYERERE. Edited by Colin Legum and Geoffrey Mmari. Mkuki Na Nyota, Dar es Salaam; Africa World Press, Trenton USA; and, James Currey, London. Published in association with the Britain-Tanzania Society. 1995. Clothbound £35. Paperbound £11.95. Special offer price to readers of ‘Tanzanian Affairs’: Clothbound – £10 from James Currey, 54B Thornhill Square. London NI IBE.

The British Empire had many achievements. One which is rarely cited is the remarkable group of leaders who led its colonies to independence. Had these colonies been fortunate enough to inherit power at the same time they would have been among the tallest on the world stage. Liberation movements attracted many intellectuals who might otherwise have taken careers other than politics. The quality of British education at home and in the colonies contributed to their formation. When history is written Julius Nyerere will rightly occupy one of the foremost places in this galaxy along with Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, Kaunda, Lee Kwan Yew and others.

This book is neither a biography nor the orthodox collection of eulogy produced on the retirement of an eminent figure. It is a scholarly compilation of some 14 essays covering his ideas, the policies that followed from them and their application to Tanzania during the 30 years of his leadership. It merits attention as one of the few attempts to analyse in depth and with objectivity the achievements of a very poor country immediately after it assumed control of its own destiny.

Nyerere has many qualities of heart and head. Huddleston, in his contribution places stress on his humility, austerity and dedication. Mmari reminds us that he did not lack determination. His attachment to his Catholic faith is an important factor in his life. Above all the theme is repeated that he is a thinker and a mwalimu (teacher) hence that honorific has been bestowed on him permanently uniquely among political leaders who have generally preferred to emphasise their power and leadership. Gandhi, Nehru and Mao were Asian leaders of an earlier generation who also had a vision of creating a New Society and of moulding a new man. Needless to say they differed in the essentials of that vision. Nyerere had a vision of building a more perfect society and a better individual in Tanzania based on African roots and socialism which encompassed Fabian humanist Marxist ideologies. Some day it is hoped that a study comparing Nehru and Nyerere will be made as these charismatic leaders had much in common. Nehru died in harness. Nyerere, having retired from office is still with us, active in the public service. Among their achievements, as Green points out in his contribution, is that much of the political engineering they accomplished continues to survive – a rare occurrence in post independence societies.

The gaining of independence from colonial rule was seen by the leadership as a new dawn when everything could be achieved. In the euphoria they believed that the same enthusiasm and the same willingness to sacrifice that enabled the ouster of foreign rulers would continue indefinitely. This would provide the motivation for the revolution to be brought about in the social structure and the economy. It was soon discovered that human nature and habits cannot be radically altered nor can vested interests be removed without enormous effort and education over a period of time. Too often unable or unwilling to confront this task the post-colonial leadership has moved back to authoritarianism. In many cases this was the penultimate stage before military rule. Nyerere realised he could not achieve his goals by using the system left by the British. As Kweka explains he believed a one-party state would better serve the entire nation. Democracy would be preserved by ensuring freedom of discussion, a policy debate and a choice of candidates for Parliament. In reality the party became all powerful and power and decision making were centralised. The one-party state instituted in 1965 was eventually dismantled in favour of a multi-party system in 1992. By that time Green states that sturdy institutions, a plural society and faith in the system had been firmly implanted. Legum, while acknowledging the achievements, prefers to remain sceptical about the future.

The overall thrust of Nyerere’s philosophy is enshrined in the Arusha Declaration of 1967. This emerged after much debate but it was essentially the distillation of Nyerere’s own thinking over a long period and was largely imposed from above. Its facets appear in most of the chapters of the book. Irene and Roland Brown sympathetically spell out the reasons behind the perceived need for planning, for education for self-reliance and for community formation in the ‘ujamaa’ village. They and other contributors recognise that it was not so easy to implement these policies. Legum points out that, although some people had to be forced, what has been achieved with very limited coercion is indeed remarkable. India, with her partly successful Five-Year Plans and community development programmes in various forms, knows very well that revolutions in agriculture and economics do not come overnight. But they do come slowly at different speeds in different places. Enthusiasm for rural modernisation can be generated. Ultimately awareness grows with decentralisation, grassroots democracy and especially education. All this needs adequate resources. Groups and individuals have to feel that they too benefit from the revolution in the quality of life and being able to acquire goods unobtainable earlier. That is why socialism and planning do not succeed if they neglect to inject a sufficient measure of market forces. Nyerere may not have realised this till the 80’s and 90’s. But he has never lost sight of the importance of self-reliance and its relevance to independence in policy formulation. It is only in the post cold war era that this reality has been forced on many developing countries which had relied on aid-driven development.

Svendsen, writing on the economic sphere, explains how, after the shocks of the 1979-81 period, the costs of implementing the Arusha Declaration became impossible to sustain. Pride had to fight with need. As countries like India had discovered 15 years earlier, altruism does not exist in international finance and commerce. Tanzania fought a spirited battle with the World Bank and the Fund but the inevitable compromises had to be reached.

‘The development of a country is brought about by people and not by money’ as Komba asserts. To do this in Tanzania required an initial revolution which most other countries did not need. There were no rural communities. People were gathered into villages with the intention that these would eventually evolve into full-fledged cooperatives. Unlike in the soviet union and China this was done mainly by consent. It is however not clear from the book how Tanzanian society has evolved; in the desire to emphasise the unity achieved, the normal process of emergence of group identities is not clearly analysed.

The book is somewhat weak on Nyerere’s international achievements. Ramphal’s contribution highlights the Commonwealth role and touches upon Nyerere’s contribution as Chairman of the South Commission. The Commission’s contribution to the economic reform now going on around the world might not be fully appreciated in the pain of ongoing structural adjustment. Self-reliance is being accepted. Just now this is being done at the national level rather than at the multilateral level as the Commission had hoped. It is perhaps utopian to hope that the new rich will be any more altruistic than the old rich.

Nyerere was always a Pan Africanist as Ramphal points out in his reference to Nyerere’s offer to delay Tanganyikan independence to help preserve the East African Union. His outspoken statement that Tanganyika would not share the Commonwealth table with South Africa after it achieved independence in 1961 prompted the latter’s exit from the Commonwealth. Decisions on Southern Africa were not without cost to the Tanzanian economy. But they were borne bravely.

Legum explains the rationale behind the final ouster of Idi Amin and the incorporation of Zanzibar into Tanzania and how this was motivated by the same philosophy of African solidarity. The TANZAM railway may not have been a success but it was another effort in the same direction.

For anyone interested in Julius Nyerere and Tanzania this book is essential reading. It suffers from the defect of people on the inside writing about their special subject. Almost every contributor has worked for the Tanzanian Government or the University of Dar es Salaam. outsiders may feel that they have not been provided with the adequate foundation of facts and data on which the analysis is based. There is also no attempt at any comparative study of neighbouring African or other developing countries. This would have provided some benchmarks against which judgements can be made. These are however minor points against the carefully drawn and relatively objective picture that is projected and is retained by the reader. The Mwalimu’s legacy is indeed that of his ideas. Maybe some of them need to be updated. But the basic thrust which comes through loud and clear still remains valid for Tanzania and indeed for many other nations.

Eric Gonsalves

UONGOZI WETU NA HATIMA YA TANZANIA. Julius K Nyerere.

Published by Zimbabwe Publishing House. 1994

This is a short book but one which seems to be of exceptional significance. Its launch in the late Autumn of 1994 created such interest that the first printing became unobtainable in a matter of days. When the author addressed a meeting of the Press Association in March this year, at which he was to return to its major theme, over 800 people are reported to have attended.

Readers in the UK might wonder what all the fuss is about. We have become accustomed to the attacks of Edward Heath on his successor and on the seeming reluctance of Margaret Thatcher to show much enthusiasm for hers. But this is of a different order. Nyerere is the ‘father of the nation’; he led the movement for independence; he presided over a Party which, whatever its internal di visions, presented to the public a sense of unity in building a peaceful nation, free from racism, tribalism and religious intolerance, a nation seen as an example to the rest of the world, even if its economy ran into major problems. Moreover, Nyerere retired voluntarily with the status of a world statesman. Ten years later, though the economic framework to which he had committed himself is fast being dismantled, and though there are those in Tanzania who dismiss him as a figure of the past, he retains great influence among large sections of Tanzanian society.

The thrust of the book is a passionate defence of the united Republic and the main features of its constitution. Nyerere believes there are those working to split the Union into the two constituent parts that existed in colonial times. He points out that the present borders of Tanzania represent virtually the only example of a post-colonial state which has borders different from those determined by the colonialists and borders which have reunited people of the coastal area and the islands who had been divided by imperial force. He argues that, once the Union were split into two parts, there would be a danger of a descent into regionalism and into divisions based on religion. which of us in Europe, looking at events in the former Yugoslavia, can confidently say this is wrong?

But Nyerere goes much further. He accuses the then Prime Minister and the then Secretary General of the CCM – both since moved to posts of lesser importance – of conniving in these moves. They are alleged, with much documentation, to have defied the policy of their own ruling Party, undermined the authority of the President and done this to further their own personal political ambitions. He says that this would not worry him so much if he could see signs of an effective opposi tion party. As it is, without such an opposition, he thinks it even more important that the CCM should look to the strengthening of its internal democracy. Failing that, he sees the danger of dictatorship of the kind he observed in a neighbouring country.

The book is of importance in the lead up to the first multi-party general election. It must be of interest to all students of Tanzanian Affairs. I understand that an English translation will be available shortly.

Trevor Jaggar

THE DARK SIDE OF NYERERE’S LEGACY. Ludovick S Mwijage. Adelphi Press. 1994. 135 pages.

It is common knowledge that a secret intelligence service was very active in Tanzania during the Nyerere years and, as a result, a number of people were detained and some were ill-treated. Most of this book is devoted to the I exciting’ (as the publisher describes it) story of these detainees. The author made no secret of his opposition to the one-party state and in 1983 fled, first to Kenya and then to Swaziland when he knew that he was in danger of arrest. He describes in dramatic detail how he was then abducted, treated very roughly, and taken back to Tanzania via Mozambique and how he was then detained there.

Part of the book skims hastily over scores of other cases of injustice, reported at the time by Amnesty International, and perhaps inevitable in a system in which democratic differences of opinion were suppressed and in which, as in the case of Zanzibar, violent revolution seemed to be the only way of bringing about change.

The author began as a teacher in Bukoba. After his release from detention he fled to Rwanda I then Portugal and is now, apparently, in Iceland studying for a degree in social sciences with Britain’s Open university! – DRB

LIMITED CHOICES. THE POLITICAL STRUGGLE FOR SOCIALISM IN TANZANIA. Dean E McHenry Jr. Lynne Rienner Publishers. 1994. 283 pages. £33.95.

This book looks at the endeavour by the political leadership in Tanzania to establish a socialist state. Its coverage is wide and quite good in my opinion, and it includes some developments almost as recent as its year of publication.

One thing which impressed me was its tile ‘Limited Choices’. The author was clearly trying to tell something impressive about Tanzania but at the end of it I felt that he still wished to tell a bit more than he actually did. The theme of the work is very much like the experience of Tanzania and the Tanzanians; they tried to achieve something significant by pursuing socialist policies but in the end they do not have much to show for it.

McHenry shows that Tanzania had few logical options other than pursuing the strong appeal of the socialist ideals which had been opted for through the Arusha Declaration. He isolates a number of factors essential either as the vehicles to achieve socialism or define its objectives in Tanzania. These include a standard of socialist morality in the leadership, democracy, equality, rural cooperatives, the parastatal sector and self-reliance. The author’s finding is that at the end of the period under study, none of them had been achieved to any commendable standard. Socialist morality, and even commitment by the leadership had been virtually abandoned. But McHenry does not indicate that the choice of socialism should be regretted.

He does not blame the socialist option for the country’s economic failure; he puts the blame on the agreement with the IMF’ and the conditions attached to it. As evidence he points to the fact that Tanzania did make some progress after the Arusha Declaration. But serious decline came in with alarming consistency after the signing of the agreement with the IMF’ in 1986. He shows further that the trend in Tanzania’s development has been just like that of other countries in subSaharan Africa, including Kenya, which never contemplated a socialist option.

McHenry’s work is very rich in its factual account of Tanzania’s political and socioeconomic development. But somehow it leaves you with the impression that the author has been too uncritical of the country generally. While blaming the IMF’ can be justified, it is not easy to understand the author’s total reluctance to try and apportion blame to local factors like mismanagement, corruption and other factors which may not necessarily concern policy, but which may nevertheless affect economic performance, irrespective of whether the policies have been socialist or not, and irrespective of the IMF conditions.

In fact the author has sometimes appeared to be too sympathetic to Tanzania. Thus, while showing quite graphically the overall decline in incomes even before the IMF, he makes no attempt at all to explain that decline. Instead he tends to view it rather positively because there was, simultaneously, an apparent decline in income inequality!

Most writers about Tanzania have found the dominance of Julius Nyerere extremely difficult to avoid. McHenry’s work, while not being an exception, must be commended for its reasonably successful attempt to draw attention to the role of persons other than Nyerere. In fact he even asserts rather boldly that, shortly after initiating socialist policies, Nyerere surrendered his ‘proprietary rights’ over socialism to the party as a collective unit. Unfortunately, the author does not assess whether indeed the party ever accepted socialism as an objective. That assessment is necessary in view of the virtual abandonment of the Arusha Declaration (through the Zanzibar Resolution of February 1991) barely six months after Nyerere’s exit from party leadership.

McHenry categorises Tanzania’s socialists, particularly in the political leadership, into ‘ideological’ and ‘pragmatic’ socialists, each struggling for control, while Nyerere maintained a midway position between the two. I find this categorisation rather disturbing. Some of the people categorised as pragmatic socialists and most of the things they have stood for are not considered as socialist, at least not in Tanzania. They may have been pragmatic but certainly not socialist. Perhaps the author made a misleading assumption that, because of Tanzania’s commitment to socialism, the entire leadership consisted of socialists only.

There are a few inaccuracies but they are negligible as far as the main thrust is concerned. But while commending the author for the effort he made to authenticate his sources he could have done a little better if he had tried to cross check what he read in the government-owned Daily News with other sources including the independent papers which emerged after 1990. Some of them are in Kiswahili, which could be a limitation to some researchers, but not to McHenry; each chapter in the book opens with its own all encapsulating Swahili proverb.

All in all this is a work well worth reading. Even if you disagree with the author’s views, arguments or conclusions his work will certainly tell or remind you about things concerning Tanzania which you may have overlooked.

J T Mwaikusa

ARMED AND DANGEROUS. MY UNDERCOVER STRUGGLE AGAINST APARTHEID. Ronnie Kasrils. Heinemann. 1993. 374 pages. £6.99.

MBOKODO. INSIDE MK – MWEZI TWALA. A SOLDIERS STORY. Ed Benard and Mwezi Twala. Jonathan Ball Publishers, Johannesburg. 1994. 160 pages. South African Rands 19.99.

These two action-packed and well-written books tell parts of the same story – what it was like to be involved in the armed struggle against South African apartheid. And, as Tanzania was an early headquarters of the African National Congress (ANC) to which both main authors belonged, Tanzania gets more than a mention.

Ronnie Kasrils was head of ANC military intelligence. He was, called the ‘Red (because he was a dedicated communist) Pimpernel’, South Africa’s most wanted man. He is now Deputy Minister of Defence in the South African government. For him his period in Tanzania (he was also in the Soviet Union, Cuba and East Germany for training and in Angola, Mozambique, Swaziland and South Africa on active service) was a generally happy one, and followed an escape over a ladder on the South Africa/Botswana border. He arrived in Tanzania in a six-seater chartered plane. He started by licking stamps, and answering the telephone at the ANC’s ‘shabby office’ in Dar es Salaam. The ‘romantic town’ reminded him of Durban. He married there – ‘The colonial registrar, who was still in place in 1964, stuck by the book and refused to marry us because we did not have our divorce papers (left behind in S. Africa) but we knew the Tanzanian Attorney General, who wrote a curt note ordering the registrar to stop being obstructive!’. Later, Kasrils had to say his traditional Judaic incantation at the Israeli Embassy in Dar es Salaam when he heard that his father had died back at home.

Tanzania in the 1960’s was the centre of much radical political activity. ‘An unforgettable event’ Kasrils wrote ‘was an address to 200 people by the legendary Che Guevara at the Cuban Embassy …. I met him later as I was sitting on the harbour wall. He was smoking a large Cuban cigar; it was his striking features, almost feline, that set him apart from ordinary mortals’.

Kasrils also met, sometimes on the verandah of the New Africa Hotel, such personalities as Oliver Tambo, the Shakespeare-loving Chris Hani, Joaquim Chissano, Jonas Savimbi ‘the gentle Malcolm X’ and many others. For Mwezi Twala, the person whose experiences are described in the second book, (‘Mbokodo’ is a Xhosa word for a grinding stone and was used to describe the security branch of the ANC’s armed wing – ‘Umkhonto we Sizwe’) Tanzania was a very different place. As was the ANC. Mr Twala is now an organiser for the Inkatha Freedom Party in South Africa.

He was a dissident from an early age having organised a strike in his primary school! And when, as a training officer in the ‘Umkhonto we Sizwe’, he sometimes disagreed with policy, he was inclined to say so. The result was that he was brutally punished in ANC detention camps in Angola and later transferred, as a prisoner to Tanzania.

His first stop was Dakawa camp where some 700 South Africans were housed in two villages and a large tent community called ‘Hawaii’. Here the author was happy at first. He was elected as a camp leader and made responsible for brick making and the manufacture of prefabricated walls for the growing settlement.

But, according to the author, Chris Hani and other senior ANC officials came to the camp. Chris Hani, ‘strutted with all the arrogance of a cockerel, while barking orders like a dog. He proceeded to issue banning orders on all of us’.

He and eighteen of his friends decided to plan an escape. And their chance came when the Tanzanian contractor with whom they had been working, apparently without the knowledge of the ANC authorities, invited them for a two-day New Year break in Dar es Salaam. Conditions had not been good at Dakawa. On the way to Dar somebody pushed a coke into his hand. ‘It was the most beautiful coke I have ever tasted in my life’.

Chapter 9 of the book describes the following period in early 1990 – imprisonment in Dar es Salaam, hunger strike, appeal to foreign embassies – and Chapter 10 describes the escape, helped considerably by friendly Tanzanians, to Malawi and eventually, after the release of Nelson Mandela, to South Africa. I After fifteen years absence, the changes that had taken place in Johannesburg were mind boggling’ the author concluded. ‘Everything I saw exuded wealth’.

Quite a lot of other things in these two exciting to read books are also mind boggling!

David Brewin

STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT: A TREASURY EXPERIENCE. J P Kipokola. Institute of Development studies Bulletin. Vol. 25. No 3. 1994 Sussex university. 5 pages.

The evaluation of structural adjustment (SA) is a growth industry these days. This article however has two merits – it tells the story of Tanzania’s SA remarkably concisely and it tells it from the point of view of the recipient treasury.

The lessons which have been learnt include:

– the value of an inter-ministerial technical group;

– the importance of timely action – something which Tanzania was slow to accept;

– the need to prioritize those resources with the most rapidly visible recovery impact; in the case of Tanzania agriculture, industry and transportation;

– not to postpone financial sector reforms;

– avoiding over-emphasis on exchange rate policy and interest rate structure;

– not to accelerate privatisation and thus create new monopolies owned by foreign enterprises;

– the need to continue to protect local infant industries;

– the need to be patient – DRB.

PARADISE. Abdulrazak Gurnah.

This book reached the Booker Prize Short List for 1994 – Ed

This book is about many things; the growing up of a young boy, the disintegration of traditional society under colonialism, the nature of freedom, and even a tragic love story.

At the age of twelve, Yusuf, the central character, is torn away from his family for reasons he does not wholly understand. It quickly becomes clear that his parents have become indebted to a wealthy trader – ‘Uncle’ Aziz – and that Yusuf is the payment. Khalil, who is older than Yusuf, has already suffered the same fate as him and thus attempts to protect Yusuf from his youthful naivety and vulnerability. Yusuf’s confusion is understandable as he faces up to the contradictions of his new situation. On the one hand Yusuf is forced to understand his new position in terms of a masterservant relationship; he is told that his ‘uncle’ is not his uncle, he should now call him Seyyid. On the other hand Khalil emphasises the honour of their ‘master; ‘He buys anything … except slaves, even before the government said it must stop. Trading in slaves is not honourable’.

The whole area of slavery, bondage and freedom is thus introduced into the book at an early stage and is pivotal to Yusuf’s transition to adulthood. Yusuf is presented to us as an innocent. He is passive, things happen to him, not because of him.

‘It never occurred to him …. that he might be gone from his parents for a long time, or that he might never see them again. It never occurred to him to ask when he would be returning. He never thought to ask ….. ‘

He is frustrating in his passivity; one finds oneself demanding, along with Khalil ‘Are you going to let everything happen to you all the time?’ Of course this passivity is bound up with him coming to terms with this position of bondage, and it is this that he realises that he must ultimately challenge. Yusuf cannot understand why Both Khalil and the gardener, Mzee Hamdani, have refused to take their freedom when offered. He accuses them of cowardice and impotence respectively. But of course Yusuf’ s greatest challenge comes when he realises he himself is free to go – like Khalil and the gardener he is freely n the service of the Merchant. This forces him to reconsider his position and face up to his own inability to control his life.

Yusuf’s final action is to attempt to take control and deliver himself from ‘slavery’. Of course the fact that he left one slave-master relationship for what was clearly another, means that his liberation was obviously limited. Nevertheless it was clearly a progression and was reflective of the lack of choice that someone in Yusuf’s position would have had.

The style of ‘Paradise’ is poetic. Gurnah attempts a fusion of myth, dream, religious tradition and realism. He succeeds in this, although it must be said that he comes nowhere near the poeticism and magic realism of Okri’s ‘Famished Road’. Gurnah is most successful, however, in providing a sensitive portrayal of one young boy’s transition to adulthood in a society where a legacy of slavery and an ever increasing colonial presence complicate notions of honour, freedom and bondage.

Leandra Box

“DRIVE SLOW SLOW – ENDESHA POLEPOLE”. Carlotta Johnson. !994. 91 pages. Obtainable @ £6 from Jane Carroll, Britain-Tanzania Society (which will receive receipts from sales) 69 Lambert Road, London SW2 5BB.

An account of a six-month’s return to Tanzania, Uganda and (briefly) Kenya after 17 years. Carlotta Johnson allows us to dip into her journal. And it makes evocative reading. I wanted to ask questions, to know more, to ‘see round the edges’ as one often does with the television screen. It is not an easy book to categorize, being neither a reference book for prospective travellers to East Africa, nor yet a guide for ornithologists – although it has something of interest for both. It is a very personal account of belonging and not belonging: of stranger-ness after many years away from a much loved country. It is both a questioning and an understanding of the clash of cultures. The poems between the chapters are an added bonus; this from “So, what did you go out in the world to see?”: ‘To try and understand about distance,/ separation, homecomings, here and there,/ to see what far is, discover/ if I can be at home away.’

Archbishop Huddleston has said that this book should be read by anyone who knows and loves Tanzania. It should also be read by anyone who recalls their own youthful contribution to that fascinating country, how little they learned at the time and how much they have realised since.

Jill Thompson

OTHER PUBLICATIONS

TRADE ROUTES IN TANZANIA: EVOLUTION OF URBAN GRAIN MARKETS UNDER STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT. Sociologia Ruralis. 34 (1) 1994. 12 pages.

ACCUMULATION, INDUSTRIALIZATION AND THE PEASANTRY: A REINTERPRETATION OF THE TANZANIAN EXPERIENCE. Journal of Peasant studies. 21 (2) January 1994. 34 pages.

PREVALENCE OF HIV-1 INFECTION IN URBAN, SEMI -URBAN AND RURAL AREAS IN ARUSHA REGION. K Mnyika and others. Aids. 8 (9). september 1994. 4 pages.

TANZANIA. Jens Jahn (Ed) • Fred Jahn, Munich. 527 pages in German and Swahili. 1994. £57.00. This is described in the ,Art Book Review Quarterly’ as a superbly illustrated (b & w) catalogue of traditional sculpture in Tanzania. It shows ceremonial works, figurative wood carvings, ornate staffs, furniture and masks. The text indicates the similarities in the aesthetics of Western Tanzania and southeast Zaire.

MINING AND STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT. C S L Chachage et al. Sweden. 1993. 107 pages mostly about Zimbabwe but with a section on mining and gold in Tanzania.

CONSERVATION OF ZANZIBAR STONE TOWN. Abdul Sheriff (Ed). 1994. 224 pages. £12.95. Essays on culture, history and architecture.

THE ORGANISATION OF SMALL-SCALE TREE NURSERIES. E Shanks and J carter. Overseas Development Institute. 1994. 144 pages. £10.95. This is designed for policy-makers/professionals and includes case studies from six countries including Tanzania.

TEACHING AND RESEARCHING LANGUAGE IN AFRICAN CLASSROOMS. C M Rubagumya (Ed). 1994. 214 pages comparing experiences in four countries including Tanzania. £14.95.

WHAT’S IN A NAME? UNAITWAJE?: A SWAHILI BOOK OF NAMES. S M Zawawi. 1993. 86 pages. £6.99.

ECONOMIC LIBERALIZATION, REAL MARKETS AND THE (UN) REALITY OF STRUCTURAL ADJUSTMENT IN RURAL TANZANIA. sociologia Ruralis. 34 (1). 1994. 17 pages.

SOCIAL CHANGE AND ECONCMIC REFORM IN AFRICA. Ed: P Gibbon. Scandinavian Institute of African studies. 1993. £12.95. 381 pages. Contains three papers on Tanzania – on the effect (or lack of effect) of structural adjustment on the growth of NGO’s, on education and on agriculture.

ECONCMIC POLICY UNDER A MULTIPARTY SYSTEM IN TANZANIA. Eds: M S D Bagachwa and A V Y Mbelle. Dar es salaam university Press. 1993. 218 pages. £14.95.

THE DEMISE OF PUBLIC URBAN IAND MANAGEMENT AND THE EMERGENCE OF INFORMAL LAND MARKETS IN TANZANIA. A case of Dar es salaam City. J W M Kombe. Habitat. Vol. 18. No 1. 1994 20 pages. Management of urban land can be undertaken by either state-led or market-led instruments. This paper explains, through four case studies, the extent to which the infonnal market-led sector is growing largely because of deficiencies in allocation under the old system.

SOME LESSONS FROM INFORMAL FINANCIAL PRACTICFS IN RURAL TANZANIA. A E Ternu and G P Hill. African Review of Money, Finance and Banking. 1/94. 26 pages. This paper, which is full of interesting insights, explores in some detail informal financial practices in the Kilimanjaro Region. These include the keeping of cattle for emergencies, borrowing from friends and relatives, borrowing livestock and using money lenders; it points out the lessons bankers can learn from this informal sector.

BEYOND DEVELOPMENTALISM IN TANZANIA. Geir Sundet. Review of African Political Economy. No 59. 1994. 10 pages. ‘The Arusha Declaration is arguably the most influential policy paper to came out of Africa’ this writer states and goes on to analyse theories of political economy and the nature of the ‘African state’. He questions present modes of analysis of African political systems.

RECENT DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE IN TANZANIA: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND FUTURE PROSPECTS. A J Mturi and P R Andrew Hinde. Journal of International Development. Vol. 7 No 1. 1995. 17 pages. Fertility in Tanzania is very high by world standards – a woman bears on average more than six children (it used to seven in the early 1980’s). The population growth rate is around 3%. These writers argue, in a fact-filled paper, that a further decline in fertility will depend mainly on the family planning programme.

DOCTORS CONTINUING EDUCATION IN TANZANIA: DISTANCE LEARNING. S S Ndeki, A Towle, C E Engel & E H 0 Parry. World Health Forum. Volume 16. 1995. 7 pages. This a description and evaluation of a programme of distance learning for 150 medical personnel in the Arusha, Kilimanjaro, Tanga and singida regions. The most popular module was the one on obstructed labour; the most difficult was on epidemiology. Costs were $341 per trainee or $0.38 per person in the region. The paper points out the lessons learnt.

TANZANIA DEVELOPS GAS. T land. Southern Africa Economist. October 1994. 2 pages.

ESTIMATING THE NUMBER OF HIV TRANSMISSIONS THROUGH REUSED SYRINGES AND NEEDLES IN THE MBEYA REGION. M Hoelscher. AIDS. Vol. 8. No. 11. 1994. 7 pages.

POLITICAL COMMITMENT, INSTITUTIONAL CAPACITY AND TAX POLICY REFORM IN TANZANIA. 0 Morrissey. Univ. of Nottingham. 1994. 25 pages.