TANZANIA AND THE WORLD BANK’S URBAN SHELTER PROJECT: IDEOLOGY AND INTERNATIONAL FINANCE by Horace Campbell. The Review of African Political Economy. No. 42, 1988, pp 5-18.

John (not Horace) Campbell sets out to examine a major World Bank funded urban project in the context of Tanzania’s relationship with the Bank and its attempts to influence domestic policy as a condition of further lending. Bank ideology has determined its actions, he argues, not the realities of Tanzania’s situation or the priorities of its government.

In the 1960’s urban areas grew rapidly and programmes of slum clearance and public housing failed to meet housing needs. Much development was unplanned, with half or more of the population living in squatter areas and dependent on incomes below the poverty line. The Second Plan (1969-74) included a commitment (although few funds) to provide infrastructure and housing suitable for the needs of the urban poor. In 1971 rental housing was nationalised, with the effect that the (primarily Asian) landlord class was pushed temporarily out of the housing market and no new housing was built for more than a decade.

Although the intention of providing serviced plots on a large scale to accommodate poorer families had been stated in 1969, it was not until 1972 that a decision was taken to proceed (partly, Campbell speculates, in response to worker unrest) and 1974 that World Bank funding was secured.

Phase I (1974-78) was intended to benefit c. 160,000 low income people by providing 10,600 serviced plots in Dar, Mwanza and Mbeya and upgrading squatter areas in Dar and Mbeya. In Phase II (1978-83) an additional 315,000 residents were to benefit from similar schemes in five urban areas. Campbell suggests that the Bank insistence on tendering contracts to the private sector was contrary to national policies which aimed at expanding the role of the public sector, although it is questionable whether the latter would have had the capacity to take on large contracts. The serviced plots provided were in relatively low density suburban areas and the Bank insisted on full cost recovery. Although construction for subletting was allowed, the provision of loans by the newly established Tanzania Housing Bank (THB) and its insistence on the use of ‘modern’ building materials, made the plots too costly for most poor families. The World Bank’s pressure to reduce standards of construction was not heeded until 1981.

By that time, Phase II was under way, despite the cost overruns of Phase I, the failure of the THB to account for funds and corruption in the allocation of plots. Shortages of housing for middle income families, due partly to policy neglect, encouraged them to obtain serviced plots, pushing out the poor to unauthorised and unserviced areas. Failure to consult residents gave rise to initial suspicion of upgrading, but this later proceeded with fewer problems. Following mounting cost overruns, project components were cut and the standard of services reduced. Responsibility for project management was devolved to local government, despite its lack of expertise and finance. As a result, services and infrastructure deteriorated rapidly and residents’ understandable reluctance to pay for them increased.

Campbell is correct in emphasising the dominance of project planning and implementation by the World Bank; pointing out that the serviced plots met the needs of the middle income rather than poor households; stressing the burden of infrastructure in need of maintenance; and accusing the World Bank of attributing Tanzania’s problems solely to economic mismanagement rather than external shocks. He may well be right that the Bank, despite its involvement with the country’s economic problems, was taken by surprise by the huge cost overruns that its attempt to devolve responsibility for project administration on to ill-prepared local government structures was an attempt to wash its hands of responsibility; and that its concern for the poor was jettisoned when cost recovery was threatened by rising costs. However, by succumbing to the temptation to treat the Bank as a scapegoat, he has oversimplified the explanations for what occurred in Tanzania between the mid-1970’s and mid-80’s. To apportion blame solely to the Bank is to ignore both the mismanagement which undoubtedly occurred, in, for example, the abolition of urban local government between 1973 and 1978; and the class interests within the indigenous (and not just Asian) Tanzanian population which have sought to utilise power and the spoils of public sector activities to advance their own interests.

Carole Rakodi

VILLAGES, VILLAGERS AND THE STATE IN MODERN TANZANIA. Edited by R. G. Abrahams. Cambridge African Monograph 4. Cambridge University Press.

These five papers which are based mainly on field work carried out in Tanzania in the seventies and early eighties, were first published in 1985. They give an insight into the situation pertaining in a number of rural communities at that time and the changes which came about during the post-independence era.

Developments in five disparate areas of the country during and after the villagisation programme known as Ujamaa are detailed. The impact of state intervention in village life has been considerable, and sadly, as is well known, much of the programme has been marred by failure. Poor management, mishandled funds and corruption were features highlighted in this paper.

The field work carried out by Thiele in villages close to Dodoma illustrates, as do other papers, the reluctance of villagers to engage in communal farming activities on collective plots. Priority was always given to their own areas and labour allocation to other work was given a distinctly low priority. The fact that communal farms have been frequently sited on the poorest and most inaccessible land does not also contribute to good production as is evidenced by the poor yields achieved in a number of villages which were listed.

The paper by Lwoga, the only contribution by a Tanzanian, based on work in the vicinity of Morogoro, shows how the State imposed its will and disregarded the views of villagers until the Prime Minister’s Office was able to make a second intervention.

In his paper Walsh outlines the problems associated with traditional leadership, both before and after independence, and how the influence of traditional authority lingered to the detriment of the community as a whole, in spite of the fact that the role of chieftancy had been abolished at the time of independence. The complicated and interweaving relationships within a community were further illustrated by Thompson who related the unsuccessful efforts of a well educated young leader from the town when pitted against the traditional beliefs of the villagers.

These various papers show that the aim of Julius Nyerere, widespread socialism has not been achieved in Tanzania. Reluctance on the part of rural communities to take part in communal activities has been clearly shown and the original aspirations of the State that each village would have a collective farm of a significant area have not been met. Merchant enterprises, such as the village lorry and shop, have often been more successful, but the examples shown indicate that such success was generally limited. Lack of spare parts for vehicles and the frequent absence of basic supplies, poor accounting and corruption, have all contributed to poor results. However, examples in two papers show what can be achieved by good leadership. The resilience and organisation of the local schoolmaster in one instance and the village chairman in the other, were largely responsible for the success achieved. The value of education was also evident in some cases and, more particularly, when this applied to a Village Manager. Thompson also illustrates the extent to which education and urban background undoubtedly contributed to the failure of one politician.

These papers are valuable contributions to the story of rural development in Tanzania during a particular post-independence period. It is to be hoped that later field work by the authors will give a further insight into more recent programmes and achievements.

Basil Hoare

ZANZIBAR TO TIMBUKTUU by Anthony Daniels. J. Murray. 1988.

The first two chapters of this book are devoted to Tanzania, and it is important in the sense that, as there is not a vast library of literature (either non-fiction or intelligent fiction) which deals with contemporary Tanzania, anything in print is liable to be seized upon as some sort of guide to the country, past as well as present.

Despite the fact that it has already had some good reviews, it is not an impressive offering. The trouble is that Daniels really wants sensation at every turn, and in Tanzania he reckons that the best way to obtain this effect is to highlight the misery and wretchedness and the way society has deteriorated in the past quarter century. So we are given a seemingly endless list of iniquities. In Dar es Salaam, for example, we are told that Africans neglect their gardens, the telephones don’t work, the potholes on the road are so bad that you need a four-wheel drive vehicle and the thieving is such a problem that you have to have locked doors, barred windows and even ‘steel gates constructed across windows.

To be fair to the writer he does try occasionally to even up the picture. He admits that ‘this violence is un-characteristic of Tanzanians’ and that ‘I knew them as gentle and forgiving people’. The problem is that he is keen to rush through Africa, from one country to another, hardly pausing to take breath, that he never stops long enough to analyse either people or social situations. Daniels is plainly aware of the ambivalence in many of the scenes he describes. The Tanzanians, though gentle, he declares, can behave extremely badly, even dishonestly to one another ‘no real trust existed between them’. ‘This is Tanzania, this is Tanzania.’

But with full respect to his lively and often amusing style and picturesque phrase, this simply will not do. If there are contradictions in people’s characters then the good writer explores them and helps us to understand the ambivalence. If he had ever done this, or even attempted it, this book would be ten times more worthwhile. The sad truth is that there is nothing in this hasty tour of Africa that is really substantial. Daniels has clutched at straws, many of them brightly coloured and diverting, but straws just the same, and blown away by the wind as they should be.

There is undoubtedly a fashion for travel books which titillate the palate with the slightly grotesque, and invite us to look with our comfortable western eyes at various morsels of Third World decay. But in these pictures there is scant truth to life. It is a pity that Daniels’ undoubted descriptive talents have not been used to produce a book of greater balance and some real depth.

Noel K. Thomas

AGRICULTURE AND DEVELOPMENT IN AFRICA: THE CASE OF TANZANIA by Goram Hyden, Universities Field Staff Report 1988/89 No. 5. pp 10. $4. 00

This report was written following a short visit to Tanzania in June 1988 funded by USAID. It is in two parts. The first is an analysis of Tanzania’s predicament. It can be summarised by a table and two quotations.

Graph of table data (not in original publication)

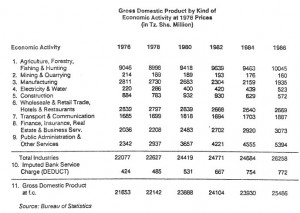

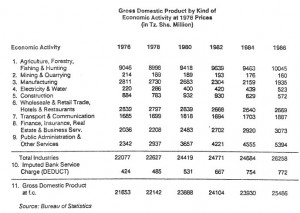

Gross Domestic Product by Kind of Economic Activity at 1976 Prices (in Tz. Sha. Million)

Economic Activity 1976 1978 1980 1982 1984 1986

1. Agriculture, Forestry,Fishing & Hunting 9,046 8,998 9,418 9,639 9,453 10,045

2. Mining & Quarrying 214 189 189 193 176 160

3. Manufacturing 2,811 2,730 2,683 2,304 2,159 1,935

4. Electricity & Water 220 286 400 420 439 523

5. Construction 884 783 932 930 629 572

6. Wholeseale & Retail Trade, Hotels & Restaurants 2,839 2,797 2,839 2,668 2,640 2,669

7. Transport & Communication 1,685 1,699 1,818 1,694 1,703 1,887

8. Finance, Insurance, Real Estate & Business Serv. 2,036 2,208 2,483 2,702 2,920 3,073

9. Public Administration & Other Services 2,342 2,937 3,657 4,221 4,555 5,394

Total Industries 22,077 22,627 24,419 24,771 24,664 26,258

10. Imputed Bank Service Charge (DEDUCT) 424 485 531 667 754 772

11. Gross Domestic Product at f.c. 21,653 22,142 23,888 24,104 23,930 25,486

Source: Bureau of Statistics

The table shows GDP growing less than 20% in 10 years – but three quarters of that growth comes from ‘public administration and other services’. Agriculture has apparently grown (but can we believe the statistics?), as has ‘finance, insurance, real estate and business services ‘; manufacturing has clearly declined.

The two quotes are the following:

In brief, the decline of the Tanzanian economy between 1973 and 1985 must be ascribed to a widespread decline in production beginning in the agricultural sector; it spread to manufacturing because imports to keep the industries going became more and more difficult to purchase with falling agricultural revenues. This situation was aggravated by the adherence to the Basic Industry Strategy which encouraged capital investments in new, often expensive and ill-conceived plants. This limited the scope for allocating scarce foreign exchange in existing industries which were often forced to operate at very low levels of available operational capacity.

It is paradoxical that Tanzania, a large country with low population densities, poor initial infrastructure, and population concentrations mostly in the areas bordering on other countries, should have devoted a smaller share (averaging about 7% between 1970 and 1985) of its resources to transport and communications compared to Kenya (12%).

The second part of the report, under the heading ‘Tanzanian Agriculture since Liberalisation’, consists of thinly disguised prescription. Priority No. 1 is maintenance of the road and rail networks. The second priority is to cope with ‘institutional shortcomings’, notably the failures of the marketing authorities and the National milling Corporation. However, ‘this must be accompanied by a strengthening of other institutions, including the co-operatives’ (how?), and Hyden also advocates ‘district based development trusts’ such as the Njombe District Development Trust. The third priority is more investment in agricultural research, but also more effort to ensure that the results of this research are used. This leads him to conclude that ‘agricultural production in the years ahead will increasingly be led by large-scale farmers’ who will be mainly ‘retired party and government officials …. cultivating 10-50 acres … in the vicinity of large urban centres’! In this way Hyden repeats his distrust of ordinary Tanzanian farmers. A similar mistake characterised his 1980 book, when, using unhelpfully aggressive language, he wrote of the ‘uncaptured’ peasantry and the need to ‘capture’ them. Somehow Hyden’s belief in market forces deserts him when it comes to small farmers. Yet his own analysis provides the clues to an alternative. If the district and trunk roads are maintained and the railways do the work they were built for and if basic consumer goods are available up-country, then Tanzanian farmers, just like those everywhere else in the world, will produce and sell.

Andrew Coulson

QUEEN OF THE BEASTS. An ITV ‘Survival Special’ broadcast on March 17th 1989.

The lion has always been a potent symbol. The European hunter who came to the area in 1913 is shown in photos with his foot on a lion’s mane. He seems to think of himself as a ‘Super lion’. By 1921 most of the lions had been shot and the scarcity of lions was the stimulus for making Serengeti, the size of Northern Ireland, a National Park. Since then fortunate visitors have seen the magnificent scenery and the vast herds of grazing animals and have got close to prides of resting lions.

I remember seeing such a pride. There were so many friendly exchanges, lickings and head rubbings that I was tempted to get out of the car and join in, especially as one lioness was lying on her back asking to be stroked!

Visitors accept lion society without questioning, but scientists, comparing it with the life style of more solitary cats have been puzzled. This ‘Survival Special’ film is the result of a recent two year project by Richard Mathews and Samantha Purdy. This involved them in danger, considerable discomfort and a great deal of drudgery but it was well worthwhile.

We saw the Serengeti at all times and all seasons; the migration of the huge herds of wildebeest and the animals left behind, especially the lions driven to tackling ostrich eggs, unsuccessfully and robbing cheetah of their prey, successfully.

One of the most exciting sequences was taken during a four day and night trek. With the aid of binoculars, cameras and film adapted for night viewing they showed us a pride at its most active. For their study the scientists kept records of individual lions. They noted and drew the nicks in their ears and the spots on their muzzles; and they listened to bleeps from electronic collars fitted to some of the lions. All this was shown with an enthralling sound track and traditional African music in the background.

The picture emerged of two groups of lion society; one being the small group of unrelated males who live together temporarily and the larger matriarchal group with only one or two adult males. By hunting strategically, large prey can be brought down, but there are other reasons for grouping. The females of the matriarchal pride are all related; they will feed one another’s cubs, and we even saw one wounded lioness who could not share the hunt share the kill.

While he is in residence the adult male is a protector, an amiable consort and a tolerant father, but about two years later he is ousted by a mature younger male or males. We saw two, who had been members of a ‘bachelor’ group, drive away the resident male. Although he put up a token fight at the edge of his territory little harm was done, The newcomers entered the new pride and drove out all the nearly mature males, again without bloodshed.

After that a vague menace became a horrifying reality. The newcomers, finding the resident lionesses unwilling to accept them, killed all the cubs they could find. Two days later the bereft lionesses came into season and after a while accepted the newcomers.

This apparent descent from nobility to savagery is disturbing but all lion behaviour has a purpose. Their usual corporate care of the cubs and even a wounded lioness is not as consciously generous, nor is the slaughter of the innocents as casually cruel as we might imagine from an anthropomorphic viewpoint.

As for us?

It is only thanks to some far seeing and caring members of our species who made the area a national park, to the scientists and film makers of today, and to the people of Tanzania who are responsible for the region that we can enjoy watching ‘The Queen of Beasts’ in her natural setting and reflect on how the ‘super lions’ can be reconciled among themselves and with nature. I am now going to ask ITV for a repeat!

Shirin Spencer

MAKONDE: WOODEN SCULPTURE FROM EAST AFRICA. From the Malde Collection. An Exhibition (April 2 – May 21. 1989) and Seminar (April 15, 1989) at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford.

The exhibits are separate pieces about 18 inches or more high, mostly columnar, worked to a smooth finish in black hardwood, mainly bearing individual artists’ names, and dated between around 1940-1970.

At first I was somewhat baffled, attracted and repelled. The often twisting, intertwining elongated figures variously distorted and even abstract yet disturbingly realistic fell into no category I was familiar with. But I was fascinated. Gradually I began to see meaning in the strangeness. The postures and activities portrayed found an echo in my own experience. There was common ground.

Then I was lucky enough to talk to Mott Malde, the collector of the pieces (We hope to publish an article on the way in which the collection was made in our next issue – Editor), and I began, after he had helped me with some stylistic puzzles, a little to enter the world of the Makonde and to identify with the themes which preoccupied them. The ‘big-headed teacher’ talks animatedly to the eager and respectful ‘little’ students who cluster round him; (size expressing importance is a familiar concept in art); a woman gives birth; a mischievous ‘spirit’ taunts and upsets two human figures; the ‘spirit’ meant to be protecting the fruit crop yields to the temptation of the succulent fruit and opens his (huge) mouth, greedily eating whilst a large turd falls from his anus (he is punished by diarrhoea ?!); ‘He who would not listen’ portrays a young man mournfully surveying his limp, ineffective penis, and ‘She who would not listen’ shows a woman whose flat, hollowed stomach suggests infertility. For the moment I am leaving out the few masks which are displayed. They come into rather a different category, I think , and require a more strictly anthropological approach than the one I am taking in these few notes.

During the last century the impact of Europeans (missionaries, traders, etc.) stimulated the Makonde to develop further their traditional wood carving. In response to direct requests they made small pieces, usually port raying ordinary everyday domestic activities. But from the 1940’s onwards they developed a more liberated, independent and individual style, using their own imagination and corporate myths to express their own unique from of life. They felt free to express fun and ribaldry, the seriousness of teaching the young the pain and joy of sexuality and reproduction, and the vulnerability of humans to the caprice of the ‘Spirits’. Different styles emerged, but most seem to be based on the tree trunk, a column of wood with the figures either carved in relief leaving the solid wood intact, or – quite breathtakingly – hollowing out the wood leaving sinuous intertwining figures of immense delicacy and inventiveness, resulting in a most satisfying filigree design. Sometimes the abstraction is so extreme one responds entirely to the aesthetic pleasure of the flowing lines weaving wonderfully balanced shapes, using both external and internal surfaces. But (almost) always, on close inspection, one realises that limbs, faces, hands and feet are intricately carved and the whole is alive with the active human or animal form.

Not surprisingly this work became popular with visitors who wanted to buy it. Various outlets were used, including of course, airports, and this has given rise to what seems to be a misconception. Because the pieces are readily saleable at airports, which therefore stimulates further production, the derogatory term ‘airport art’ has been in this case misapplied. Mr. Malde was very insistent that all his pieces are carved by genuine artists, who decide the subject themselves and who, like most practising artists, are pleased to have their work bought.

The SEMINAR was held to discuss ‘Issues of Colonialism, Primitivism, Exoticism and Western Attitudes Towards Indigenous Art’. The well-qualified speakers talked learnedly and fairly about primitive art (is it art ?) but, I felt, from a purely detached Western perspective. As I listened I became increasingly uncomfortable. These were people of meticulous scholarship, who clearly respected indigenous art and judged it worthy of study on its own terms, but whose emotional distancing, their retreat almost into academic concepts gave the implicit message that of course a direct and instinctive response to the sculptures themselves was for a European impossible. I profoundly disagree. Undoubtedly the more one knows of the background and life of the Makonde the more one’s understanding and appreciation of the sculptures increases. And certainly we delude ourselves if we claim, arrogantly, completely to understand what we are seeing. But having said that, I feel if we lay aside (as far as we ever can) our own cultural conditioning, and humbly allow ourselves to respond naturally and simply to the carvings, a great deal of their fundamental meaning is communicated to us. I am sure that our common humanity, our shared hopes, fears, joys and longings provides a common ground from which we can enter into the spirit of the work of art. If it is passionately and honestly made, we can have a passionate and honest response to it. Then it becomes both ‘other’ and ‘familiar’.

This is an excellent exhibition, and large and varied enough to give one a rich experience of a modern art form of culture different from our own, engrossing in its own unfolding into a new form of an old society. We must thank the Oxford Museum for mounting it.

(The exhibition will be in Preston in July and August, Southampton in September and October, Bristol in December and January, Glasgow in January and February and Leicester from February to April 1990 – Editor)

Kathleen Marriott